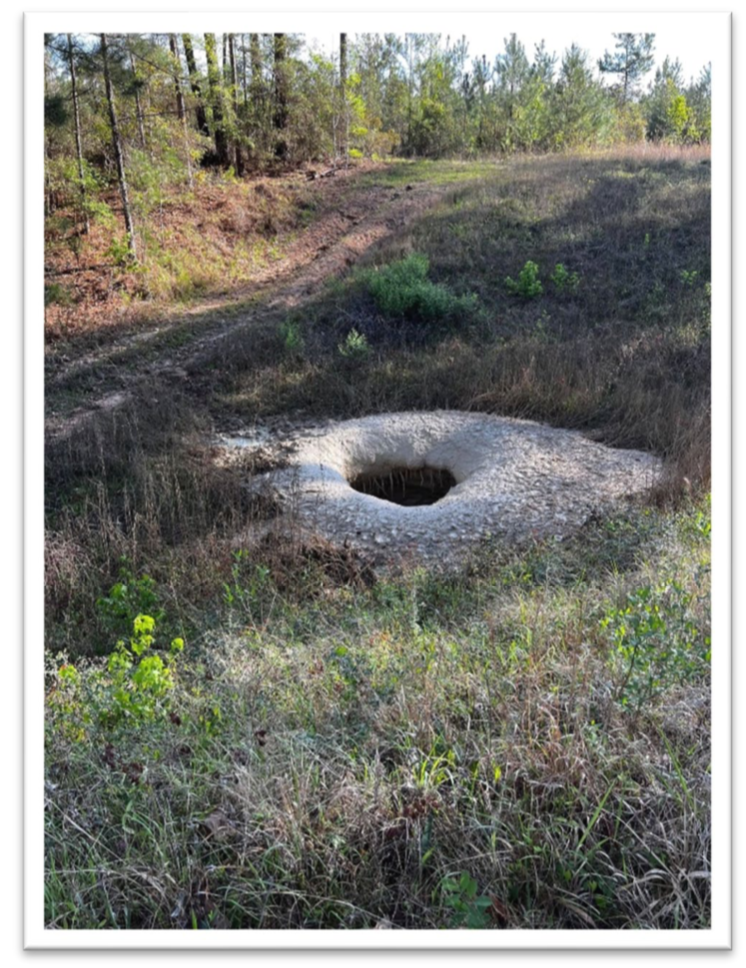

Back in the Spring, personnel were preparing to conduct a prescribed burn in Polk county. The burn boss along with an operator were doing some final prep work to ensure that the containment lines were adequate and the site was ready for the burn.

Back in the Spring, personnel were preparing to conduct a prescribed burn in Polk county. The burn boss along with an operator were doing some final prep work to ensure that the containment lines were adequate and the site was ready for the burn.

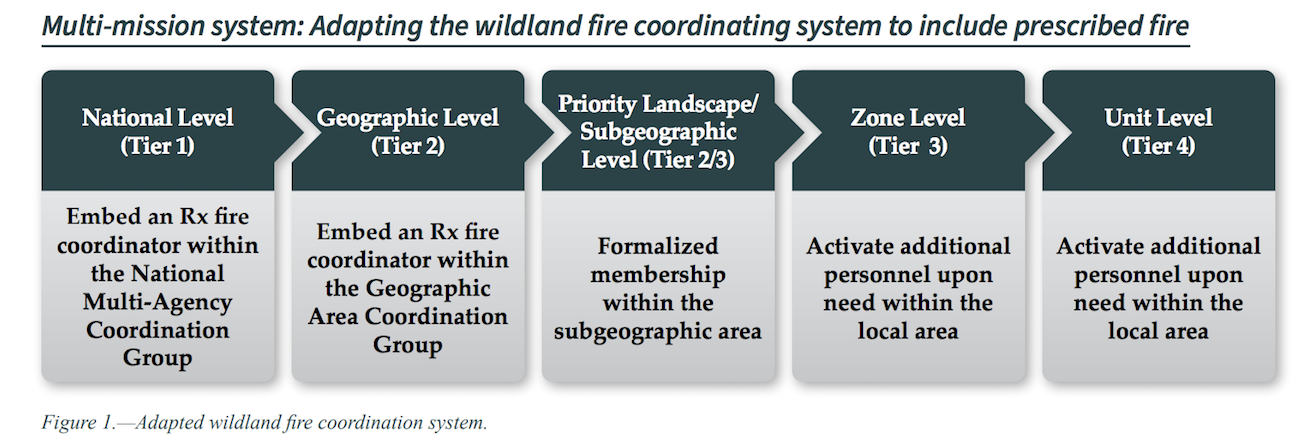

This summer the National Prescribed Fire Resource Mobilization Strategy was released. The plan calls for six prescribed fire implementation teams to be created that will incorporate prescribed fire practitioners and expertise into a management structure. This concept would support the implementation of prescribed fire at multiple organizational and complex levels. These teams would be tailored to meet specific needs and facilitate multiple projects simultaneously. Each function that supports the implementation of prescribed burning can be scaled up or down at any level, to ensure that logistical, financial, planning, safety, and public information are staffed accordingly.

This summer the National Prescribed Fire Resource Mobilization Strategy was released. The plan calls for six prescribed fire implementation teams to be created that will incorporate prescribed fire practitioners and expertise into a management structure. This concept would support the implementation of prescribed fire at multiple organizational and complex levels. These teams would be tailored to meet specific needs and facilitate multiple projects simultaneously. Each function that supports the implementation of prescribed burning can be scaled up or down at any level, to ensure that logistical, financial, planning, safety, and public information are staffed accordingly.

[Read more…] about National Prescribed Fire Resource Mobilization Strategy

In 2017, a group of prescribed fire researchers (including me!) set out to answer the age-old question…is prescribed fire liability…prescribed fire’s scapegoat? Check out this work that talks about the Edwards Plateau Prescribed Burn Association escape prescribed fire lawsuit here.

(J.R.Weir,U.P.Kreuter,C.L.Wonkka,etal.,LiabilityandPrescribedFire:PerceptionandReality,RangelandEcology&Management, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2018.11.010)

Although use of prescribed fire by private landowners in the southern Great Plains has increased during the past 30 yr, studies have determined that liability concerns are a major reason why many landowners do not use or promote the use of prescribed fire. Generally, perceptions of prescribed fire−related liability are based on concerns over legal repercussions for escaped fire. This paper reviews the history and current legal liability standards used in the United States for prescribed fire, it examines how perceived and acceptable risk decisions about engagement in prescribed burning and other activities differ, and it presents unanticipated outcomes in two cases of prescribed fire insurance aimed at promoting the use of prescribed fire. We demonstrate that the empirical risk of liability from escaped fires is minimal and that other underlying factors may be leading to landowners’ exaggerated concerns of risk of liability when applying prescribed fire. We conclude that providing liability insurance may not be the most effective approach for increasing the use of prescribed fire by private landowners. Clearly differentiating the risks of applying prescribed fire from those of catastrophic wildfire damages, changing state statutes to reduce legal liability for escaped fire, and expanding landowner membership in prescribed burn associations may be more effective alternatives for attaining this goal. Fear of liability is a major deterrent to the use of prescribed fire; however, an evaluation of the risks from escaped fire does not support perceptions that using prescribed fire as a land management tool is risky. Prescribed burning associations and agencies that support land management improvement have an important role to play in spreading this message.

EPPBA LAWSUIT

In the second case, insurance provided to members of a PBA in Central Texas contributed to the initiation of multiple lawsuits following an escaped fire that negatively affected the use of prescribed fire by some landowners. The specifics of this incident and its aftermath were obtained through interviews with people involved in the lawsuits and through analysis of legal briefs and motions filed with the Sutton County court. In March 2011, a contractor who was neither certified as a burn manager nor insured was hired by a pair of private landowners in Sutton County, Texas to conduct a prescribed burn on their property during a burn ban. The contractor had recently become a member of the local PBA and counseled the landowners who hired him to also join the PBAs so that they would be covered by the prescribed fire insurance provided by the association to its members. To comply with the PBA’s insurance requirements, the contractor also filed a burn plan with the PBA. In addition, these people requested an exemption from the county judge to apply prescribed fire during the burn ban. The judge ruled that only certified burn bosses would be granted a variance and denied the request. In contravention to this ruling, the contractor nevertheless proceeded with the planned burn. In preparation for the burn, the fire crew pre-burned backfires along firebreaks to create blacklines on the downwind side of the planned fire. During blackline burning, the wind direction shifted, causing the fire to ignite a stand of extremely dry juniper trees. Embers from the burning junipers were blown outside of the burn unit and initiated an escaped fire that burned approximately 405 ha on the contracting landowners’ property and three adjacent properties. Even though there was no major property damage or injury, the escaped fire led to multiple lawsuits. Three plaintiffs filed lawsuits involving the landowner’s property, where the fire started; the PBA; and a founding member of the PBA who had disapproved the proposed burn. Two insurance companies became involved in claims by the three landowners including the company that underwrote the PBA’s prescribed fire insurance policy and the company that provided insurance for the landowners who had signed the contract for the burn. Initially, the latter insurance company stated its policy did not cover prescribed fire damage but ultimately agreed to pay for the claimed damages to settle the litigation. Once the insurance companies agreed to pay for the specified damages, the defendants were dropped from the lawsuit. The ultimate effect of the lawsuits for the unapproved burn was that the insurance company withdrew coverage of the PBA’s prescribed fire insurance policy. Importantly, the insurance company omitted to include an “illegal activities” clause in the policy with which the insurance company would not have had to pay any claims because this was a fire conducted against

the ruling of a county judge. The PBA was named in the lawsuit due to wording in its bylaws that erroneously made it appear that the PBA did contract burning for landowners. As a result, numerous PBAs rewrote their bylaws to emphasize they only provide education, training, and opportunities for landowners to conduct prescribed burns and to clarify that PBA membership does not provide the right to burn outside state laws or prescribed burning guidelines set by the PBA. The fear of liability from this one incident has dramatically reduced the use of prescribed fire in the region, even though the escaped fire and subsequent lawsuits stemmed from an illegally and improperly conducted burn. One informative statement came from an individual who was a PBA member and had burned regularly but became concerned about risk following the outcome of the lawsuits stemming from this illegal burn in which he had no part. He stated: “How could I get started burning in 2003 without checking my insurance coverage for hostile (escaped) fire? There was no visceral ‘fear.’ Also, there were no escapes on my30-plus fires. Now the fear is intellectual. With it comes inertia. No one wants to have an escape, and we all know that with any fire there is always that risk. Why doesn’t planning allay that fear? The damage done by the arrogance of the escaped fire in 2011 hangs around our shoulders like a cloak.”

This individual experienced risk reversal and stopped using prescribed fire because of concerns about the actions of others—in this case a lawsuit initiated by a neighbor because his land was burned and due to the existence of an insurance policy against which he could claim. Most other people in the area who had used prescribed fire and were not covered by the PBA’s insurance policy continued to burn undeterred.

Chris Schenck works as the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Statewide Fire Program Leader for the Wildlife Division. He also serves on the Texas Department of Agriculture Prescribed Burn Board and, most importantly, he is a friend, colleague, and admirably passionate about fire’s role on Texas rangelands.

How did you get introduced to fire? In 1979 as a college student at Utah State University (the other Aggies), I got a summer job as a Fire Prevention Technician on the Wasatch Cache National Forest. The long time Fire Management Officer Neff Hardman took me and others under his wing and gave us lots of opportunities in fire and fuels. In the fall when most students were in a dull work study job several of us would be burning brush piles in the afternoon on the forest till dark. Later when ranching in Idaho I tried burning windrows of sage brush with little experienced in “controlled burning.” I found out after burning down a Union Pacific drift fence and part of the neighbors pasture how little I actually knew about Prescribed Burning.

What started as a really good summer job became a thirty plus year career in Fire and Aviation with the US Forest Service. I continued to learn and progress in many areas in fire during my time. I was blessed to work throughout much of the country and even Alaska and Australia. I worked on Hand Crews, Engines, Helicopter Crews and Incident Management Teams. I also worked in Structural Fire and as an Emergency Medical Technician. Later I was a Fire Management Officer of a District and then a National Forest.

I did make a pretty good living in fire suppression and we did a fair amount of Prescribed Burning in the shoulder seasons and traveling throughout the south in the winter. A lot to times on real big wildfires, I wondered if what we were doing really made a difference. Seemed like those wildfires were going to go out when they wanted to, but we would take credit for it any way. I did notice many times when we had conducted Prescribed Fires and other fuels treatments and big wildfires ran in to those areas we had a better chance to actually manage the fire.

The US Forest Service has a mandatory retirement of age 57 for folks in fire. This was tough for me as I had just about figured out what I was doing at that age. Fortunately a job came along with Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. The State Fire Program Leader for the Wildlife Division is the job I am currently in. This is perhaps the best job I have ever had in fire management. I am paid well travel all of Texas and don’t have to supervise anyone. More so my supervisors have empowered me to try to make a difference in the Division and there for in Prescribed Fire in Texas. The Division burns about 30-40,000 acres on Public lands and provides Technical Guidance for Prescribed Fire on 6-12,000 acres of private lands each year. Perhaps this work in prescribed fire is a little penance for all the fire suppression of my youth.

How early do you start planning for a prescribed burn? A year in advance would not be too soon to start planning for prescribed burns. The Division allows burn plans to stand without major revision for 5 years. This would signify a 5 year rotation for fire on the burnable land in a given project. Our Burn Plans also receive technical review by another Burn Boss. We have developed burn plans with short turn around for Private Land Technical Guidance Prescribed Fire within a month. These are usually low complexity Prescribed Burns. Most important are site visits and developing a fuels and weather prescription.

What’s most unique about a post-fire environment? I think looking at the various fire effects and how the phoenix rises from the ashes so to speak. Certainly the immediate or first order fire effects is shocking to most viewers. Less so to me as I have a pretty good idea that with in a growing season new plant growth is coming. I have noticed in many ecosystems many native plants are hidden by the invasive species only to flourish in the post fire environment. Even in stand replacing fires in some fuel types we see results within that growing season. I am often disturbed by the terms used by the media about “destructive wildfires” or “total devastation.” Certainly these fires are destructive to people, infrastructure and livestock. The ecosystem is often very resilient and comes back to more properly function stages. That’s where the phoenix comes from.

In your opinion, what makes a successful fire? Success is multi-faceted. At the most basic level is that we kept the fire in the box and folks were safe in doing it. At the most complex levels is that we achieved our most desirable management or ecological goal. In between there are a variety of measures of success. For land owner Technical Guidance, first entry burns I often here the land owner say ”At first I was a little worried about burning, but now I see that under the right conditions it can be done.”

On or public lands larger projects after multiple entries it is rewarding to see quantifiable changes in forage production and type, or actual improved water yields. On landscape prescribed fires it is great to see communities able to sustain and manage a wild fire because of strategic prescribed fire and fuels reduction programs.

Who or what would you never burn without? There are a few things: A good prescribed burn plan with a sound fire behavior and weather prescription. Good preparation of fire lines or holding features. Good dependable people and equipment. I truly believe that 70% of success in prescribed fire is in planning and preparation. If you have that the mindful execution of the plan makes the other 30% of the burn day enjoyable. Even with an occasional spot or slop over, you had a plan to catch it before it was an escape. That’s the way 99% of prescribed fires go

If you have ever heard of prescribed burning in Texas, then I am sure you have heard of thee Dr. Butch Taylor. He goes by Dr. Charles A. Taylor, Jr. on his numerous publications (I’m telling you folks, he wrote the book, literally). Butch is a tremendous friend, mentor, and colleague and I hope you enjoy his story as much as I have. We could all learn something from Butch.

How did you get introduced to fire? Fire was first presented to me as a viable range management option when I was in 4-H and involved in range judging. Later, as an undergraduate majoring in range science, fire was again presented as a viable range management option. However, both of these experiences were more hypothetical and involved no practical application of fire to the landscape. In fact, in the mid-and late 1960s, fire was viewed as being harmful to the ecosystem by the general public and even by some range professionals. Also, growing up in a “dry-climate” (Pecos County), I was not able to experience or view any evidence that fire was something that could be used in range management (I never saw any evidence of a fire-culture and didn’t know if it existed).

Surprisingly, the army provided my first experience of the benefits of fire. I entered the Army in 1968 and was sent to Fort Sill for artillery training. I’m sure I was the only range science major in the class. A big part of our training was live-firing artillery into the impact zone. They would load us in trucks and transport us to the firing range where we would be assigned a target and we would have to send in fire missions via radio. This training occurred during July and August and it was extremely hot and dry. Coming from the Trans-Pecos region of Texas, I had never seen grass production like what was produced at Fort Sill (i.e., tall grasses such as big bluestem, Indian grass, little bluestem, etc.).

One extremely hot, dry, windy day, while firing artillery rounds into the impact zone a fire broke out. The wind was blowing towards us and even though there was some distance between the impact zone and our location, it was obvious the fire would be upon us quickly. The Colonel in charge of the exercise quickly gave the order to load-up in the trucks and get out of the area. While everyone else was scrambling to get into the trucks, I stood and watched in amazement as the fire traveled across the landscape with flame lengths over 20-feet high. My attention was quickly brought back to the issue at hand as the Colonel screamed in my ear to get my b_ _ on the truck, right now!

Later I asked the Colonel how often they had fires during the training sessions. He commented he had been stationed at Fort Sill for over 5-years and his recollection was that it had burned every summer.

Later I was stationed at Fort Hood, where I observed the same results of frequent fire as I observed at Fort Sill. And, then I spent a year in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam and while most of the land was used for rice-farming, there were zones where farming was not used due to frequent and intense combat. These areas were dominated by tall grasses which burned frequently during the hot, dry- season.

Because of these observations in the Army, I started setting fires under hot, dry conditions as soon as I got in a position of authority.

How early do you start planning for a burn? There are general guidelines that can be used in the process for prescribed burning. A general guideline is to start prescribed burn planning 2-3 years prior to implementation of the burn. The application of prescribed fire is not rocket science, but it can be complicated. One major reason for this is that actual burn days are limited within any particular year, and the burn plan should be planned and developed well ahead of the actual fire (e.g., wait until optimum weather conditions and then be in a position to pull the trigger at a moment’s notice). Preparation of the burn unit is also time consuming. For example, fire-line preparation results in piles of brush along the fine-line. Brush piles contain large amounts of 10-hour fuels. Diameter of these fuels range in size from ¼” to 1” in diameter. They are light enough to be picked up by the energy of the fire but large enough to continue burning a considerable distance downwind (i.e., I’ve experienced spot fires starting 600-feet downwind from brush piles). Brush piles should be burned during safe conditions. Bottom line is that a comprehensive burn plan may contain over 20-important items that have to be developed, planned, and explained prior to the burn; this takes time.

What’s most unique about a post-fire environment? The answer to this is somewhat a function of the goals and objectives of the landowner. For example, if a manager is mostly trying to improve cattle production then fires that reduce woody plant cover and increase grass are usually favored. If the major noxious plants are perceived to be prickly pear, ashe juniper, and Eastern red cedar, then starting prescribed fires during dry periods in the summer time can have drastic effects on the vegetative complex. Even with dense stands of juniper and pear these plants can actually be killed with the right kind of fire (i.e., reclamation burns conducted during drought). This practice of growing season burning has the most potential for increase grass production in the Edwards Plateau.

If the goal is to improve forage quality with some suppression of woody plant growth and/or mitigate wildfire frequency and intensity, then burns conducted during the dormant season under mild conditions might be the choice. Actually, very few species of plants are killed by fire. Most plants are well adapted to fire and respond in a positive manner following fire. Fire is not a one-time tool.

In your opinion, what makes a successful fire? Any fire that meets the goals and objectives of a land manager is a successful fire. The goals and objectives should be clearly explained in the burn plan and a prescription developed to meet those goals and objectives. It should also be remembered that grass is the major component of the fuel to carry the fire. And that grass can be used for forage or fuel. So a successful fire not only requires a comprehensive burn plan but also effective grazing management.

Who or what would you never burn without? I would never burn without a weather forecast. Over the years I’ve seen more people get into trouble starting fires without having a comprehensive weather forecast (this includes prescribed burns, burning brush piles, trash burning, etc.). A close second would be a good comprehensive insurance policy.