West Texas Rangelands is devoted to delivering and transferring the latest research and scientific studies to landowners, stakeholders, and practitioners!

In our new blog series, Published to Pasture, we will feature published journal articles from academic, state, and federal researchers that are not only impactful and meaningful for our rangeland stakeholders, but will also empower and enhance overall knowledge of Texas rangeland systems!

Thinking like a grassland.

What does this mean to you?

Well, to Dr. David Augustine from the USDA-ARS Station in Fort Collins, CO and others, it means large-scale movement of many species. This large-scale movement enables the Great Plains evolved strategies to contend with drought, floods, and even wildfires…in a nutshell….extreme variability in weather resulting in low forage production.

Currently, our pattern of land ownership and use of Great Plains grasslands challenges native species conservation. For example, too much management is focused at the scale of individual pastures or ranches, limiting opportunities to conserve landscape-scale processes such as fire, animal movement, and metapopulation dynamics.

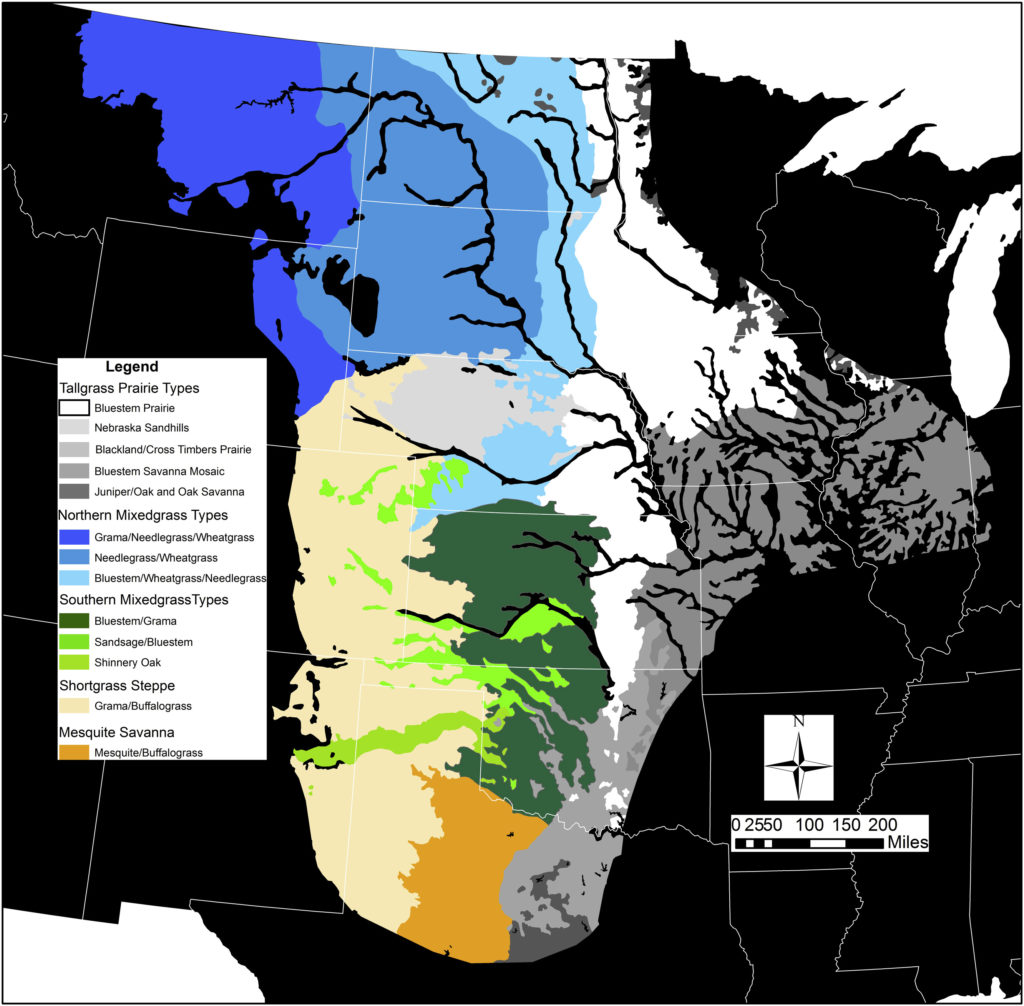

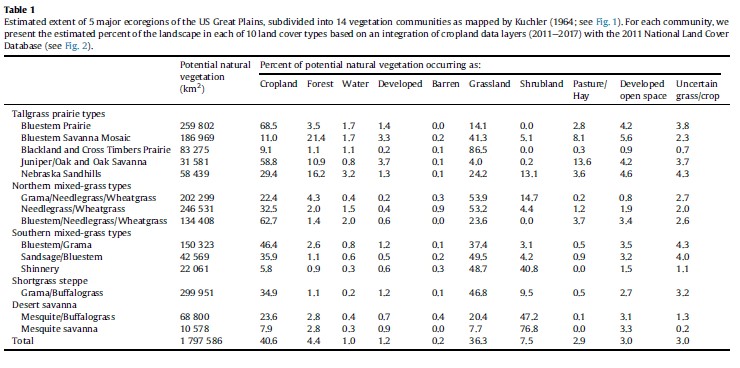

“Figure 1. Potential natural vegetation of US portion of the North American Great Plains, adapted from Kuchler (1964).”

“Estimated extent of 5 major ecoregions of the US Great Plains, subdivided into 14 vegetation communities as mapped by Kuchler (1964; see Fig. 1). For each community, we present the estimated percent of the landscape in each of 10 land cover types based on an integration of cropland data layers (2011e2017) with the 2011 National Land Cover Database.”

Opportunities to increase the scale of grassland management include:

- Spatial prioritization of grassland restoration and reintroduction of grazing and fire.

- Finding creative approaches to increase the spatial scale at which fire and grazing can be applied to address watershed to landscape-scale objectives.

- Developing partnerships among government agencies, landowners, businesses, and conservation organizations that enhance cross-jurisdiction management and address biodiversity conservation in grassland landscapes, rather than pastures.

Thinking like a grassland should be pretty easy for us range managers…open spaces, big country, and…thinking big!!

For an in-depth view of “Thinking Like a Grassland: Challenges and Opportunities for

Biodiversity Conservation in the Great Plains of North America”, click on this link: Thinking like a grassland Augustine et al., 2020 REM.

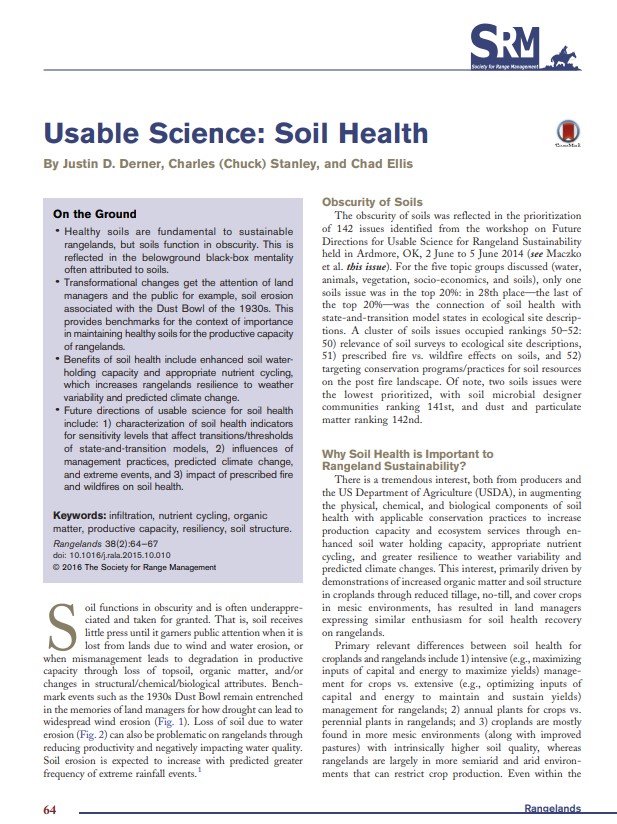

Soil Health…kind of catchy, right?! I agree. And, so do thousands of other range managers and landowners. It’s the buzz word of the century and it’s here to stay. So what do we know about soil health and how the heck can our ranchers use it?

Today, we will be looking at 2 relatively recent articles on soil health. First, “Usable Science: Soil Health” written by Justin Derner, Chuck Stanley, and Chad Ellis. Secondly, we will look at “Soil Health as a Transformational Change Agent for US Grazing Lands Management” written by Justin Derner, Alexander Smart, Theodore Toombs, Dana Larsen, Rebecca McCulley, Jeff Goodwin, Scott Sims, and Leslie Roche.

Why is soil health on the minds of every range manager these days? Easy. Dust Bowl of the 1930s was a benchmark event that changed every single range, crop, and land-man’s way of thinking. Total game changer. As Derner and others stated, “The 1930s Dust Bowl remains entrenched in the memories of land managers for how drought can lead to widespread wind erosion.” I couldn’t agree more. As range managers, we seek to learn from our mistakes – not repeat them. So now we have the most talented scientists working out the details of a very complex, obscure, and complicated science of the physical, chemical, and biological components of soil and how applicable conservation practices increase production, capacity, and ecosystem services through enhanced soil water holding capacity, appropriate nutrient cycling, and greater resiliency to weather variability and predicted climate changes. For example, utilizing novel experiments with adaptive grazing management wherein short “pulses” of grazing with a large herd followed by rest periods of more than 1 year provides experimental platforms to evaluate the efficacy of soil health monitoring efforts. Can I get an amen from the range gospel choir?! Wahoo!!! It’s about dang time!

Why is soil health on the minds of every range manager these days? Easy. Dust Bowl of the 1930s was a benchmark event that changed every single range, crop, and land-man’s way of thinking. Total game changer. As Derner and others stated, “The 1930s Dust Bowl remains entrenched in the memories of land managers for how drought can lead to widespread wind erosion.” I couldn’t agree more. As range managers, we seek to learn from our mistakes – not repeat them. So now we have the most talented scientists working out the details of a very complex, obscure, and complicated science of the physical, chemical, and biological components of soil and how applicable conservation practices increase production, capacity, and ecosystem services through enhanced soil water holding capacity, appropriate nutrient cycling, and greater resiliency to weather variability and predicted climate changes. For example, utilizing novel experiments with adaptive grazing management wherein short “pulses” of grazing with a large herd followed by rest periods of more than 1 year provides experimental platforms to evaluate the efficacy of soil health monitoring efforts. Can I get an amen from the range gospel choir?! Wahoo!!! It’s about dang time!

To summarize what the Rangelands article is talking about, here we go:

#1. What are the effects of conservation practices (e.g., prescribed grazing, prescribed fire, and brush management) on the chemical, physical, and biological components of soil health?

#2. Can the chemical, physical, and biological components of soil health be used as “early indicators” of phase, transition, and/or threshold shifts in plant communities for state-and-transition models to enhance ecological site descriptions?

#3. How can the chemical, physical, and biological components of soil health be enhanced through adaptive management to increase the resilience of soils to weather variability and changing climate?

#4. How can the soil health tool kit to provide more robust and broad assessments of soil health and/or monitoring of the chemical, physical, and biological components for land managers in a timely and responsive manner to facilitate adaptive management be expanded?

Fast forward to our next article, Soil Health as a Transformational Change Agent for US Grazing Lands Management and now is where we get to the cool nerd stuff. Current soil health is an opportunity not to focus on improvement of soil health on lands where potential is limited but rather to forward science-based management on grazing lands via

#1. Refocusing grazing management on fundamental ecological processes (water and nutrient cycling and energy flow) rather than maximum short-term profit or livestock production

#1. Refocusing grazing management on fundamental ecological processes (water and nutrient cycling and energy flow) rather than maximum short-term profit or livestock production

#2. Emphasizing goal-based management with adaptive decision making informed by specific objectives incorporating maintenance of soil health at a minimum and directly relevant monitoring attributes

#3. Advancing holistic and integrated approaches for soil health that highlight social-ecological-economic inter-dependencies of these systems, with particular emphasis on human dimensions

#4. Building cross-institutional partnerships on grazing lands’soil health to enhance technical capacities of students,land managers, and natural resource professionals

#5. Creating across-region, living laboratory network of case studies involving producers using soil health as part of their grazing land management. Explicitly incorporating soil health into grazing management and the matrix of ecosystems services provided by grazing lands provides transformational opportunities by building tangible links between natural resources stewardship and sustainable grazing management, as well as providing paths to reach broader audiences and enhance communications among producers,customers, and the general public.

Now, we can really jump up and say “hallelujah!!!!”

This is what their vision looks like:

My favorite part, is “Re-focus grazing management on fundamental ecological processes.” What a concept!!

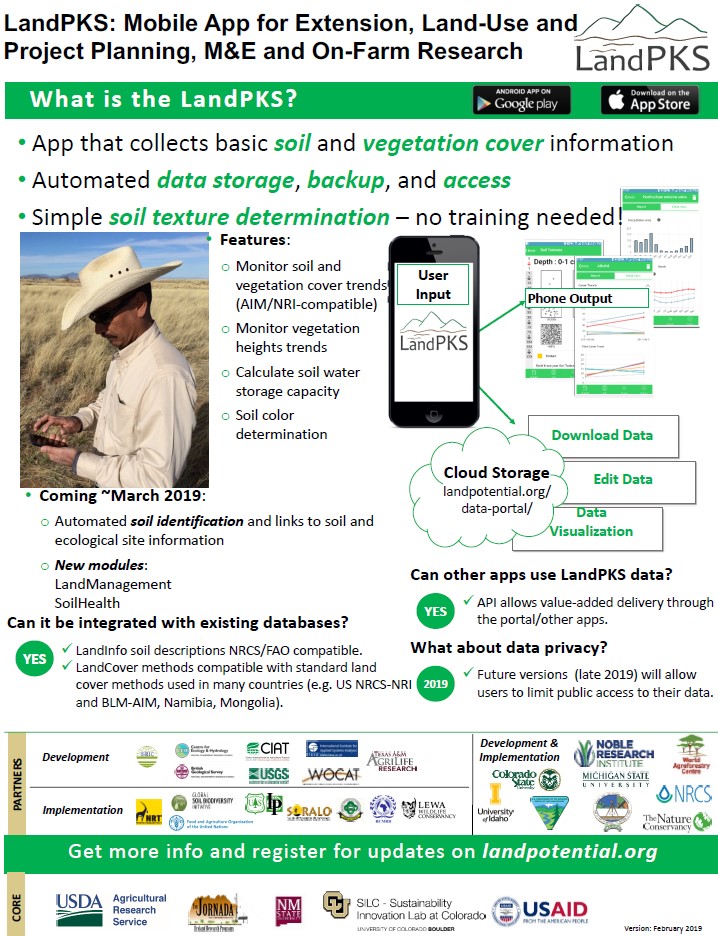

Better yet! There is an app for that! Check out LandPKS on your smartphone device and start collecting data on LandInfo, LandCover, and LandManagment!

Please click here for more information regarding this remarkable tool!

Believe it or not, Soil Health is more fun and easy than you think! We just overcomplicated it!

Believe it or not, Soil Health is more fun and easy than you think! We just overcomplicated it!

In 2017, a group of prescribed fire researchers (including me!) set out to answer the age-old question…is prescribed fire liability…prescribed fire’s scapegoat? Check out this work that talks about the Edwards Plateau Prescribed Burn Association escape prescribed fire lawsuit here.

(J.R.Weir,U.P.Kreuter,C.L.Wonkka,etal.,LiabilityandPrescribedFire:PerceptionandReality,RangelandEcology&Management, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2018.11.010)

Although use of prescribed fire by private landowners in the southern Great Plains has increased during the past 30 yr, studies have determined that liability concerns are a major reason why many landowners do not use or promote the use of prescribed fire. Generally, perceptions of prescribed fire−related liability are based on concerns over legal repercussions for escaped fire. This paper reviews the history and current legal liability standards used in the United States for prescribed fire, it examines how perceived and acceptable risk decisions about engagement in prescribed burning and other activities differ, and it presents unanticipated outcomes in two cases of prescribed fire insurance aimed at promoting the use of prescribed fire. We demonstrate that the empirical risk of liability from escaped fires is minimal and that other underlying factors may be leading to landowners’ exaggerated concerns of risk of liability when applying prescribed fire. We conclude that providing liability insurance may not be the most effective approach for increasing the use of prescribed fire by private landowners. Clearly differentiating the risks of applying prescribed fire from those of catastrophic wildfire damages, changing state statutes to reduce legal liability for escaped fire, and expanding landowner membership in prescribed burn associations may be more effective alternatives for attaining this goal. Fear of liability is a major deterrent to the use of prescribed fire; however, an evaluation of the risks from escaped fire does not support perceptions that using prescribed fire as a land management tool is risky. Prescribed burning associations and agencies that support land management improvement have an important role to play in spreading this message.

EPPBA LAWSUIT

In the second case, insurance provided to members of a PBA in Central Texas contributed to the initiation of multiple lawsuits following an escaped fire that negatively affected the use of prescribed fire by some landowners. The specifics of this incident and its aftermath were obtained through interviews with people involved in the lawsuits and through analysis of legal briefs and motions filed with the Sutton County court. In March 2011, a contractor who was neither certified as a burn manager nor insured was hired by a pair of private landowners in Sutton County, Texas to conduct a prescribed burn on their property during a burn ban. The contractor had recently become a member of the local PBA and counseled the landowners who hired him to also join the PBAs so that they would be covered by the prescribed fire insurance provided by the association to its members. To comply with the PBA’s insurance requirements, the contractor also filed a burn plan with the PBA. In addition, these people requested an exemption from the county judge to apply prescribed fire during the burn ban. The judge ruled that only certified burn bosses would be granted a variance and denied the request. In contravention to this ruling, the contractor nevertheless proceeded with the planned burn. In preparation for the burn, the fire crew pre-burned backfires along firebreaks to create blacklines on the downwind side of the planned fire. During blackline burning, the wind direction shifted, causing the fire to ignite a stand of extremely dry juniper trees. Embers from the burning junipers were blown outside of the burn unit and initiated an escaped fire that burned approximately 405 ha on the contracting landowners’ property and three adjacent properties. Even though there was no major property damage or injury, the escaped fire led to multiple lawsuits. Three plaintiffs filed lawsuits involving the landowner’s property, where the fire started; the PBA; and a founding member of the PBA who had disapproved the proposed burn. Two insurance companies became involved in claims by the three landowners including the company that underwrote the PBA’s prescribed fire insurance policy and the company that provided insurance for the landowners who had signed the contract for the burn. Initially, the latter insurance company stated its policy did not cover prescribed fire damage but ultimately agreed to pay for the claimed damages to settle the litigation. Once the insurance companies agreed to pay for the specified damages, the defendants were dropped from the lawsuit. The ultimate effect of the lawsuits for the unapproved burn was that the insurance company withdrew coverage of the PBA’s prescribed fire insurance policy. Importantly, the insurance company omitted to include an “illegal activities” clause in the policy with which the insurance company would not have had to pay any claims because this was a fire conducted against

the ruling of a county judge. The PBA was named in the lawsuit due to wording in its bylaws that erroneously made it appear that the PBA did contract burning for landowners. As a result, numerous PBAs rewrote their bylaws to emphasize they only provide education, training, and opportunities for landowners to conduct prescribed burns and to clarify that PBA membership does not provide the right to burn outside state laws or prescribed burning guidelines set by the PBA. The fear of liability from this one incident has dramatically reduced the use of prescribed fire in the region, even though the escaped fire and subsequent lawsuits stemmed from an illegally and improperly conducted burn. One informative statement came from an individual who was a PBA member and had burned regularly but became concerned about risk following the outcome of the lawsuits stemming from this illegal burn in which he had no part. He stated: “How could I get started burning in 2003 without checking my insurance coverage for hostile (escaped) fire? There was no visceral ‘fear.’ Also, there were no escapes on my30-plus fires. Now the fear is intellectual. With it comes inertia. No one wants to have an escape, and we all know that with any fire there is always that risk. Why doesn’t planning allay that fear? The damage done by the arrogance of the escaped fire in 2011 hangs around our shoulders like a cloak.”

This individual experienced risk reversal and stopped using prescribed fire because of concerns about the actions of others—in this case a lawsuit initiated by a neighbor because his land was burned and due to the existence of an insurance policy against which he could claim. Most other people in the area who had used prescribed fire and were not covered by the PBA’s insurance policy continued to burn undeterred.

In 2018, Wilmer and others published “Collaborative adaptive rangeland management foster management-science partnerships” in Rangeland Ecology and Management (check it out here). I really valued this paper, because fostering management-science relationships is what Extension is all about!

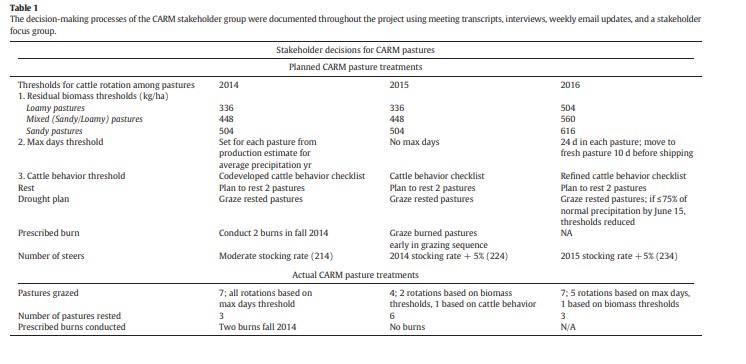

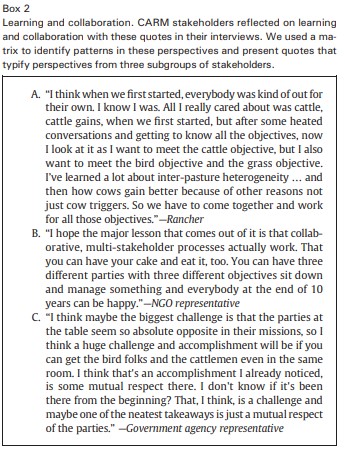

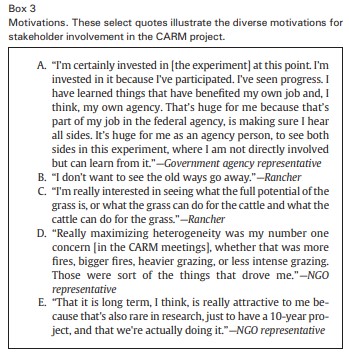

This paper is a case study, based on qualitative social data collected from meeting notes and interview transcripts recorded from ranchers and agency representatives in a Collaborative Adaptive Rangeland Management (CARM) study. In this synthetic assessment, they explored to what extent participation in the CARM experiment enabled adaptive decision making by a group of rangeland stakeholders (landowners, agencies, non-profit, etc..).

The specific objectives of this study were to 1) document how diverse stakeholder experiences and knowledge (meaning their socially constructed theories and justifications for rangeland management knowledge) contribute to the CARM project, 2) evaluate how co-produced knowledge informed management decision making through three grazing seasons, and 3) explore the implications of participation in the CARM experiment for rangeland stakeholders.

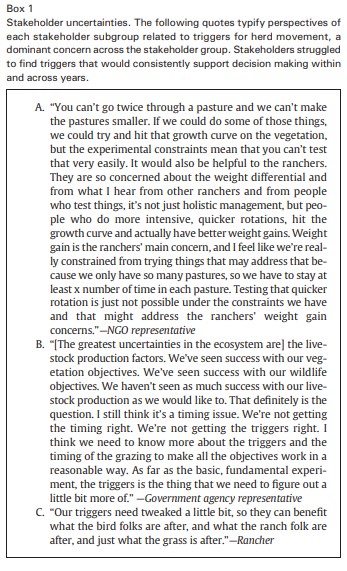

Here are some snapshot comments from ranchers, agency, and NGO reps on uncertainties, learning/collaboration, and motivations:

The authors found that this interactive process can reveal the differences among stakeholder knowledge about complex rangeland systems, but does not reconcile those differences. And that it is HIGHLY UNLIKELY that stakeholder decision-making related to cattle rotation and prescribed fire decisions will be made on data from research or experiments. However, it is likely that Collaborative Adaptive Rangeland Management (CARM) can build awareness and appreciation for the diverse ways of knowing about rangeland management. Stakeholders are more likely to utilize:

- Discussion and consideration of different reasoning for management actions

- Enhanced understanding when stakeholders are involved in the project design and monitoring data collection and presentation.

- Frequent discussion of the rational for decisions

- Presentations of multiple information sources

- Focus groups or tours that encourage sharing participants’ ways of knowing and experiences

Bottom line, rangeland management stakeholders prefer making decisions based on the broadest range of available information, INSTEAD of exclusively using scientifically derived knowledge!!!

Next, data from this paper showed TRUST among stakeholder and researcher groups may improve social learning by increasing the transparency of unique stakeholder experiences and knowledge. Stakeholder trust over time facilitated engagement and commitment from stakeholders and researchers to work toward a common goal.

So…are you a landowner, rancher, producer that agrees with this? I certainly hope so because this is all about what Extension creates, facilitates, and nurtures. Our job is to provide YOU the landowner with all the information and bring YOU to a network of stakeholders that you TRUST!

As Extension, we should:

- Make direct efforts to share and acknowledge managers’ different rangeland management experiences, epistemologies, and knowledge

- Involve long-term research commitment in time and funding to social, as well as experimental, processes that promote trust building among stakeholders and researchers over time

This all is very ironic to me, because it is what ranchers have been telling me for a long time. But, now that we have it in a published journal, maybe the other half can start listening!

I love my job. I love delivering information. I love working with ranchers. I serve at the pleasure of West Texas ranchers, and it is a an honor. Thank you!!

Our first journal article (Short–Term Control of an Invasive C4 Grass With Late–Summer Fire) comes from Rangeland Ecology and Management and was recently published by Charlotte M. Remeets and others in January 2019 (see below for full citation and pdf link).

Reemts studied yellow bluestem (Bothriochloa ischaemum [L.] Keng var. songarica [Rupr. ex Fisch & C.A. Mey] Celarier & Harlan) which, is a non-native, invasive warm-season grass commonly found throughout the southern Great Plains rangelands.

Their study takes place on two rangeland study sites, one at the Fort Hood Military Reservation and the second near Buda, Texas at the City of Austin Water Quality Protection Lands. Both sites had been unmanaged (no grazing, burning, mechanical, or chemical work) since 2000.

Reemts measured the effects of a single late-summer (burned in September 2006) fire on yellow bluestem.

At the Fort Hood site, researchers found relative frequency of yellow bluestem in burned plots decreased by 88% (74 ± 4% preburn; mean ± standard error) to 9 ± 2%) by the following year (2007) and remained significantly lower compared with non-burned plots through 2009 (burned: 14 ± 2%; nonburned: 70 ± 14%).

At the Buda site, yellow bluestem initially decreased by 57% (74 ± 5% (2006) to 32 ± 7% (2007)). UNFORTUNATELY, yellow bluestem recovered substantially by 2009 (67 ± 10%), but was still significantly lower than in unburned transects (96 ± 1%).

But, what about the grasses?! Well, the researchers looked at composite dropseed and little bluestem at the Fort Hood site, and relative frequency of these other grasses increased significantly in burned plots (compared with preburn values) (preburn: 11 ± 4%; 2009: 29 ± 7%). However, the Buda site consisted mainly of purple threeawn and Texas wintergrass and did not increase following the burn (preburn: 24 ± 6%; 2009: 22 ± 7%). Interestingly, Texas wintergrass actually decreased (for those of you looking to manage Texas wintergrass)!

Frequency of forbs increased dramatically in the first growing season after fire (Fort Hood: 15 ± 2% to 76 ± 3%; Buda: 2 ± 2% to 45 ± 5%), then decreased through the third growing season (Fort Hood: 57 ± 6%; Buda: 11 ± 4%).

So, the researchers present some very interesting data in managing yellow bluestem, but WHY the differences in results between the two sites? Well, a couple of things, the Fort Hood site had higher forage production (composite dropseed and little bluestem) at the beginning of the study compared to the Buda site (Texas wintergrass and purple threeawn). And, the Fort Hood site consisted of clay loam soils. Whereas, the Buda site was on much more shallow soils and had been previously grazed prior to 2000.

Take home message? Prescribed burning can suppress invasive, opportunistic yellow bluestem, but site conditions and previous management have a lot to do with the plant community response. It would be interesting to go back to the same sites in 2019 and look at the frequency of yellow bluestem. It would also be very interesting to burn it again!

All in a day’s work for range managers looking to promote native grass species and diversity. I encourage you to look at this paper more closely if you have the time, but if you don’t that’s what you got me for!