When we think about the effects of fire and grazing, we often focus on what’s visible—charred grasses, shifting plant communities, and changes in wildlife behavior. But just beneath our feet, a powerful shift is also happening. Fire and herbivory don’t just impact the surface—they reshape entire microbial communities within the soil, influencing how rangelands recover, grow, and function long after the flames cool off or the herd moves on.

When we think about the effects of fire and grazing, we often focus on what’s visible—charred grasses, shifting plant communities, and changes in wildlife behavior. But just beneath our feet, a powerful shift is also happening. Fire and herbivory don’t just impact the surface—they reshape entire microbial communities within the soil, influencing how rangelands recover, grow, and function long after the flames cool off or the herd moves on.

Bacteria: Small But Resilient

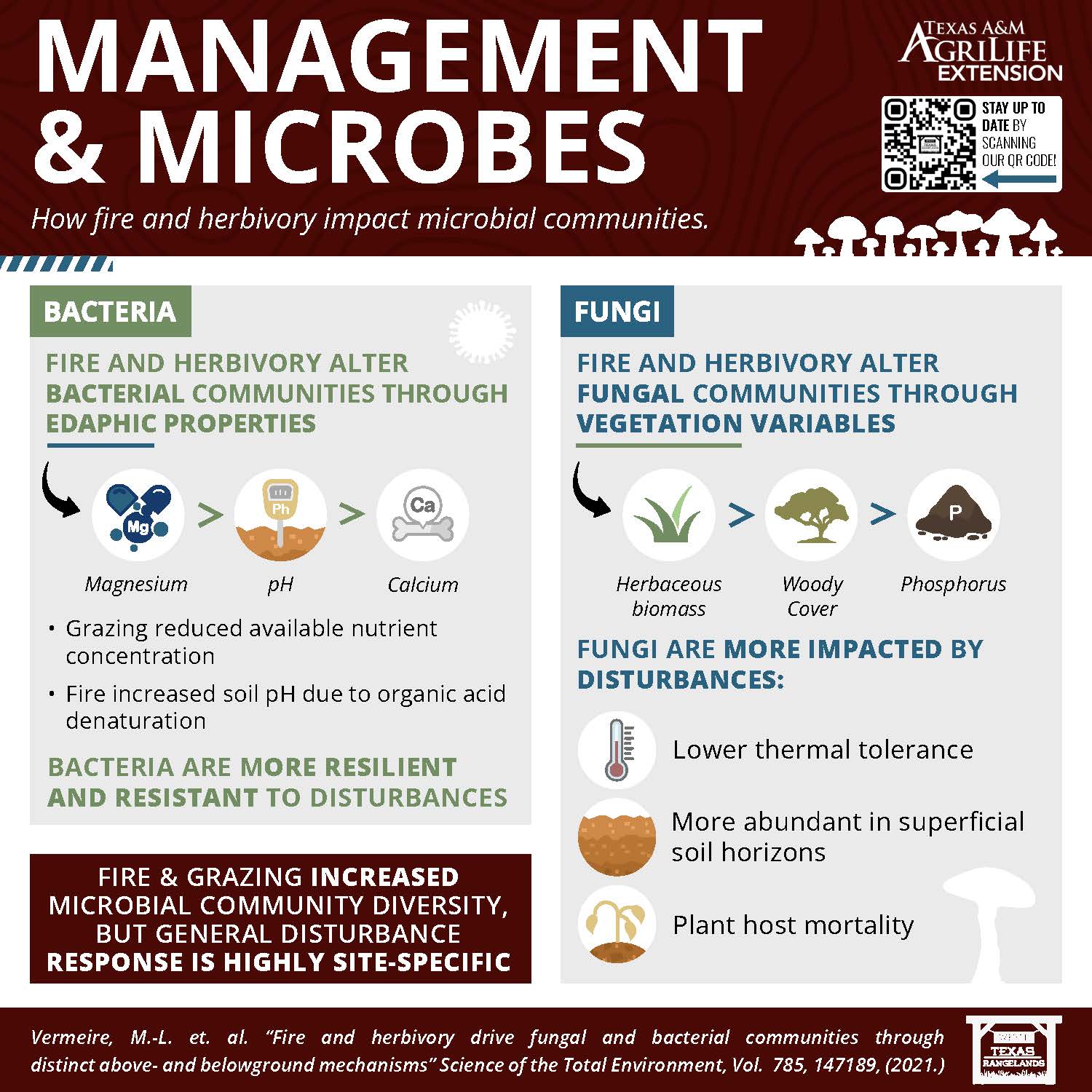

Soil bacteria are surprisingly tough. These microscopic workhorses are responsible for nutrient cycling, breaking down organic matter, and helping plants thrive. According to recent research, bacteria respond to fire and grazing primarily through changes in edaphic properties—characteristics of the soil like magnesium, pH, and calcium levels.

- Grazing reduces the availability of essential nutrients like magnesium.

- Fire raises soil pH levels, largely due to the breakdown of organic acids during combustion.

- These changes affect how bacterial communities are structured—but interestingly, bacteria are generally more resilient and resistant to these types of disturbances compared to fungi.

Fungi: More Sensitive to Change

Fungi play equally critical roles in soil health, from aiding in plant nutrient uptake to decomposing complex organic material. However, fungal communities are far more sensitive to environmental disturbances. Their composition shifts in response to vegetation variables such as:

- Herbaceous biomass

- Woody plant cover

- Soil phosphorus levels

Unlike bacteria, fungi have lower thermal tolerance and are more concentrated in superficial soil layers, making them more sensitive to changes from fire and grazing. Additionally, the loss of plant hosts due to fire can further destabilize fungal networks, affecting long-term ecosystem recovery.

The Big Picture: Diversity & Disturbance

While both bacteria and fungi are influenced by rangeland management practices, fire and grazing tend to increase overall microbial diversity. However, how each ecosystem responds is highly site-specific—what works in one system may not apply in another and definitely management history dictates future success. This underscores the need for site-based management strategies that consider both above- and below-ground impacts based on previous management stressors.

Bottom Line

Understanding how microbes respond to management practices isn’t just academic—it’s essential for building resilient landscapes that tolerate floods, fires, and time. Whether you’re a rancher, rangeland manager, or conservationist, integrating microbial insights into your strategies can help you make more informed, sustainable decisions that build profitability below and aboveground.

For more in depth information be sure to read the full study – Fire and herbivory drive fungal and bacterial communities through distinct above- and belowground mechanisms