Our grasslands are incredible ecosystems, vital for everything from supporting wildlife to producing our food. But what happens when snaps of extreme climate occur and prolonged drought becomes the new norm? A fascinating new study, dives deep into the unseen world beneath our feet to show us the progression of grassland decline under increasing aridity and desertification.

Our grasslands are incredible ecosystems, vital for everything from supporting wildlife to producing our food. But what happens when snaps of extreme climate occur and prolonged drought becomes the new norm? A fascinating new study, dives deep into the unseen world beneath our feet to show us the progression of grassland decline under increasing aridity and desertification.

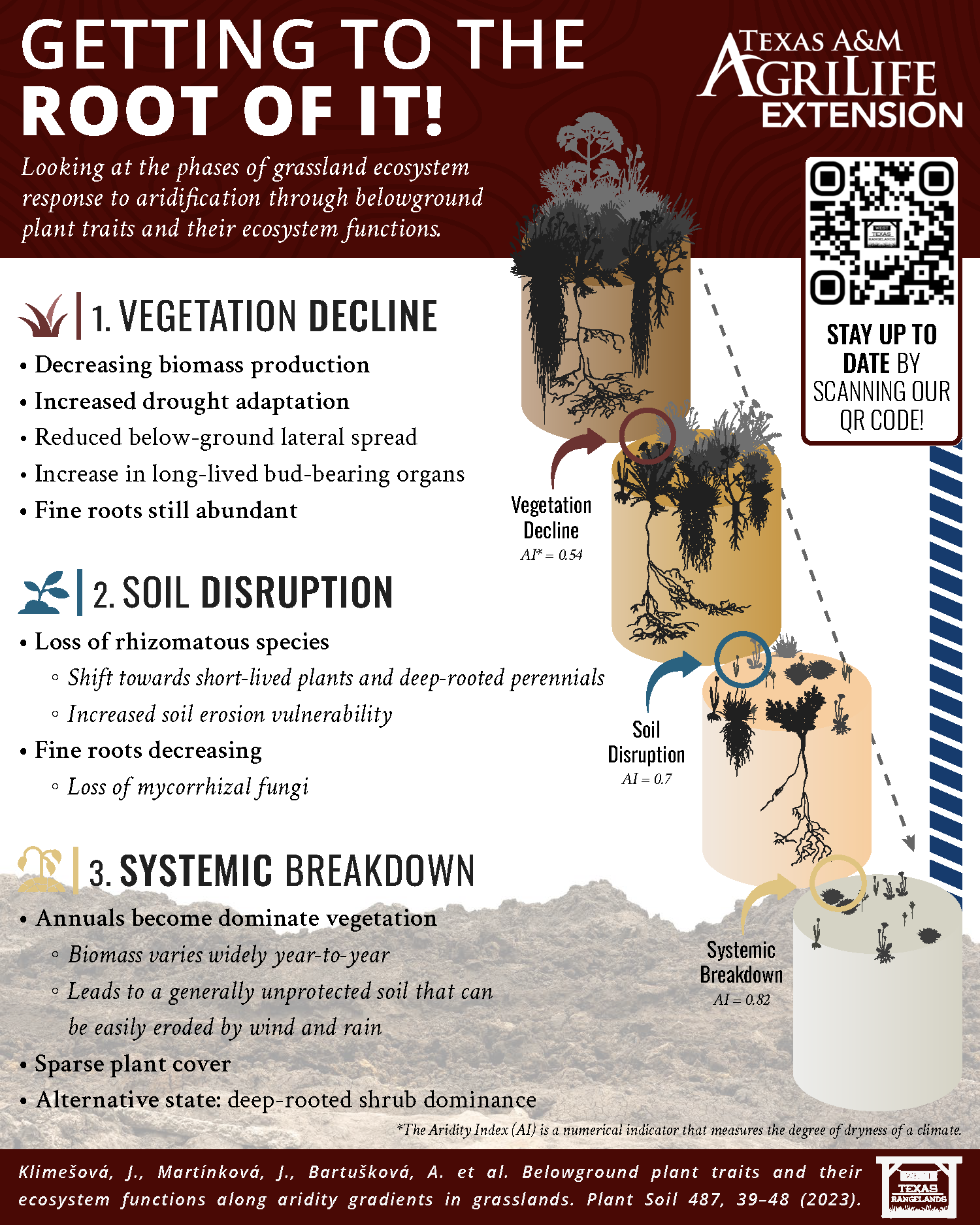

It’s not just about what we see above ground; the real story of resilience and vulnerability often lies in the soil and the intricate root systems within it. The study outlines three key phases of grassland ecosystem response to aridification, each with its own tell-tale signs, especially below ground:

Phase 1: Vegetation Decline (Aridity Index ≈0.51)

At the first signs of increased dryness, visible vegetation begins to struggle. Biomass production decreases, meaning less plant matter aboveground overall. Surprisingly, plants may initially show increased drought adaptation, trying to cope with the changing conditions. However, there’s a reduced below-ground lateral spread as roots become less expansive, and an increase in long-lived bud-bearing organs – perhaps a last-ditch effort to persist. Importantly, at this stage, fine roots are still abundant, suggesting the plant is still actively foraging for water and nutrients.

Phase 2: Soil Disruption (Aridity Index ≈0.7)

As conditions become even drier, the impact on the soil becomes more severe. This phase is characterized by a loss of rhizomatous species, which are crucial for soil stability and spreading. There’s a shift towards short-lived plants like annuals indicating a change in the dominant plant community. With less robust root systems, there’s increased bare ground. A critical change belowground is the decrease in fine roots and a loss of mycorrhizal fungi, which are essential partners for nutrient uptake in plants. This is one of the last opportunities to maintain soil health and prevent further degradation without expensive reclamation type decisions.

Phase 3: Systemic Breakdown (Aridity Index ≈0.82)

At this most advanced stage of aridification, the grassland ecosystem experiences a fundamental shift. Annuals (both forb and grass) become the dominant vegetation, leading to biomass varying widely year-to-year – a clear sign of instability. This results in unprotected soil that can be easily eroded by wind and rain, further accelerating degradation. We see sparse plant cover, and eventually, the system can transition to an alternative state of deep-rooted shrub dominance, a very different and often less productive ecosystem.

This research, from Klimešová, J., Martínková, J., Bartušková, A., et al. (2023) published in Plant Soils, highlights the critical importance of understanding what’s happening beneath the surface. By paying attention to these below-ground plant traits and their ecosystem functions, we can better anticipate and potentially mitigate the effects of climate change on our vital grassland ecosystems.