It was a spring day in Schleicher County around 1985. Dr. Landers was waiting on students to finish a range contest when he decided to do a local rancher a small favor. Twin-leaf senna (Senna roemeriana) is a toxic plant known for causing livestock poisoning, and he had spotted a patch nearby. On a whim, he dug up about a dozen plants.

It was a spring day in Schleicher County around 1985. Dr. Landers was waiting on students to finish a range contest when he decided to do a local rancher a small favor. Twin-leaf senna (Senna roemeriana) is a toxic plant known for causing livestock poisoning, and he had spotted a patch nearby. On a whim, he dug up about a dozen plants.

Curiosity got the better of him, and he cut into some of the swollen main roots. To his surprise, inside were insects in various stages of growth—from grub to adult. He sent them to Texas A&M for identification and learned that they were an extremely rare species, with the last documented collection dating back to 1923.

Could this insect have been a natural control for twin-leaf senna? He wondered about it, but, admittedly, he never followed up on the discovery.

Twenty Years Later…

Two decades later, he returned to dig up another dozen plants—this time on shallow soil where there was a plant every meter or so. He found no swollen roots, no insects, and the ranch had no history of twin-leaf senna poisoning.

Over his career, he had seen most cases of poisoning occur with young kid goats just beginning to graze. There was only one instance involving a cow, and that was on severely depleted rangeland in Sutton County. His observation is that kids learn what to graze by watching their mothers—if mom avoids twin-leaf senna, the kids usually do too.

The Real Solution: Management, Not Chemicals

In his experience, twin-leaf senna problems are almost always a management issue rather than something you solve with herbicide. Here’s Dr. Landers’ advice:

- Don’t turn young goats out into shallow soil, brushy pastures right away.

- Do let them learn to graze in your best pastures first.

- Then move them into rougher pastures once they know what’s safe to eat and have learned from mom.

By managing grazing patterns and timing, ranchers can avoid most problems without resorting to costly spraying.

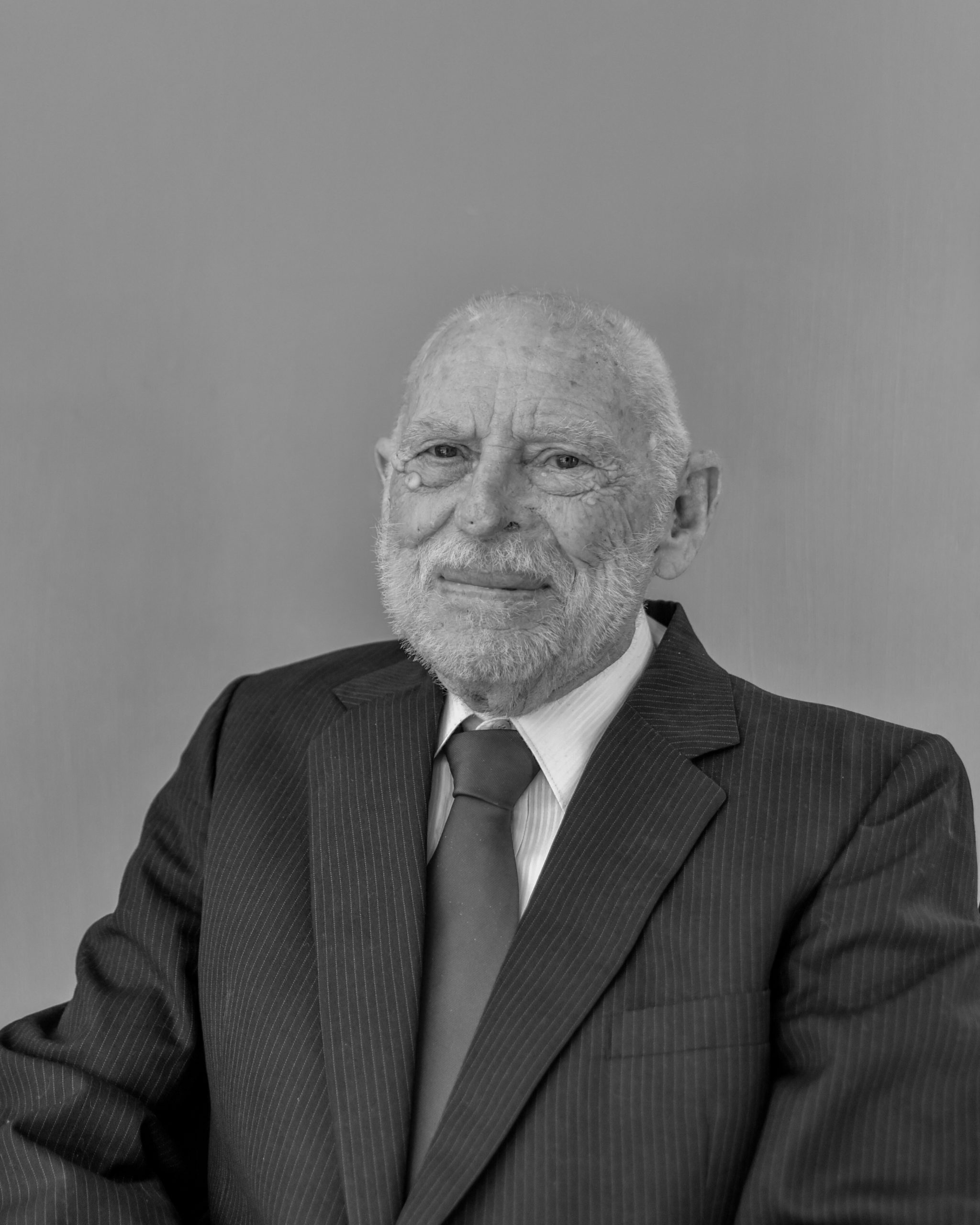

About Dr. Roger Q. “Jake” Landers, my friend, colleague, and hero.

Seen as the quintessential land steward by his peers and friends, Dr. Landers remained highly active in range management until age 91, following 57 years of impactful research, teaching, outreach, and mentorship. In 2016, he received the Sustained Lifetime Achievement Award from the Society for Range Management—just one of his many honors.

A graduate of Texas A&M University, Dr. Landers earned both his bachelor’s (1954) and master’s (1955) degrees in range management and forestry, and helped create the Texas Section Society of Management Youth Range Workshop, an annual week-long grazing management camp for high school students. After serving as a U.S. Army officer, he earned his Ph.D. in plant ecology from the University of California, Berkeley.

During 17 years on the faculty at Iowa State University, Dr. Landers also served as president of the Nature Conservancy in Iowa and as director of the Iowa Academy of Sciences. His research there led to lasting improvements in roadside vegetation management across the state’s interstate highways.

In 1979, Dr. Landers returned to Texas to serve as the range specialist in San Angelo for the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service. He went on to direct the Youth Range Workshop for 40 years, welcoming over 2,000 youth and inspiring similar programs in other states.

At his family’s Menard County ranch—renowned for brush management, proper grazing, and wildlife care—Dr. Landers continued to lead by example, opening the gates to ranchers and students alike. In 2015, his community recognized him as Menard County Citizen of the Year for his enduring contributions.

And I miss him. Dearly.