Texas endured a dramatic climatic shift in July—one that’s already rewriting the story of our drought and breaking 131 year records. But even as optimism swells, persistent vulnerabilities remind us the path to recovery is far from over.

Texas endured a dramatic climatic shift in July—one that’s already rewriting the story of our drought and breaking 131 year records. But even as optimism swells, persistent vulnerabilities remind us the path to recovery is far from over.

Over the past month, Texas has seen real progress in its drought outlook. Just four weeks ago, 30% of the state was facing moderate to exceptional drought. Today, that number has dropped to 19%, thanks in large part to improvements across the southwestern third of the state. Even the most severe categories are shrinking: extreme drought has fallen from 13% to just 4%, and exceptional drought—which once covered 6% of Texas—is now down to only half a percent.

When we step back and look at the bigger picture, 28% of Texas is still considered “abnormally dry or worse.” While that’s not ideal, it’s a noticeable improvement from 38% a month ago. These changes remind us that conditions can shift quickly—and while the state isn’t out of the woods yet, the trend is finally moving in the right direction.

The July storms will go down as some of the most historic—and heartbreaking—weather events Texas has seen in decades. Tragically, the floods claimed at least 135 lives, with the greatest toll in Kerr County, where 117 people lost their lives. Other counties were also impacted: nine fatalities in Travis, five in Burnet, three in Williamson, and one in Tom Green.

What made these storms so extraordinary were the rainfall rates. In some areas—upstream of Hunt, north of San Angelo, and south of Bertram—three-hour rainfall totals surpassed what scientists classify as a “1-in-1,000-year” event. Other places, including Menard and Burnet, experienced rainfall that matched or exceeded “1-in-500-year” thresholds. In San Angelo and between Menard and Mason, 24-hour totals pushed past the “1-in-1,000-year” mark.

These numbers underscore just how extreme and rare the storms truly were—reminders of both the power of nature and the vulnerability of the communities in its path.

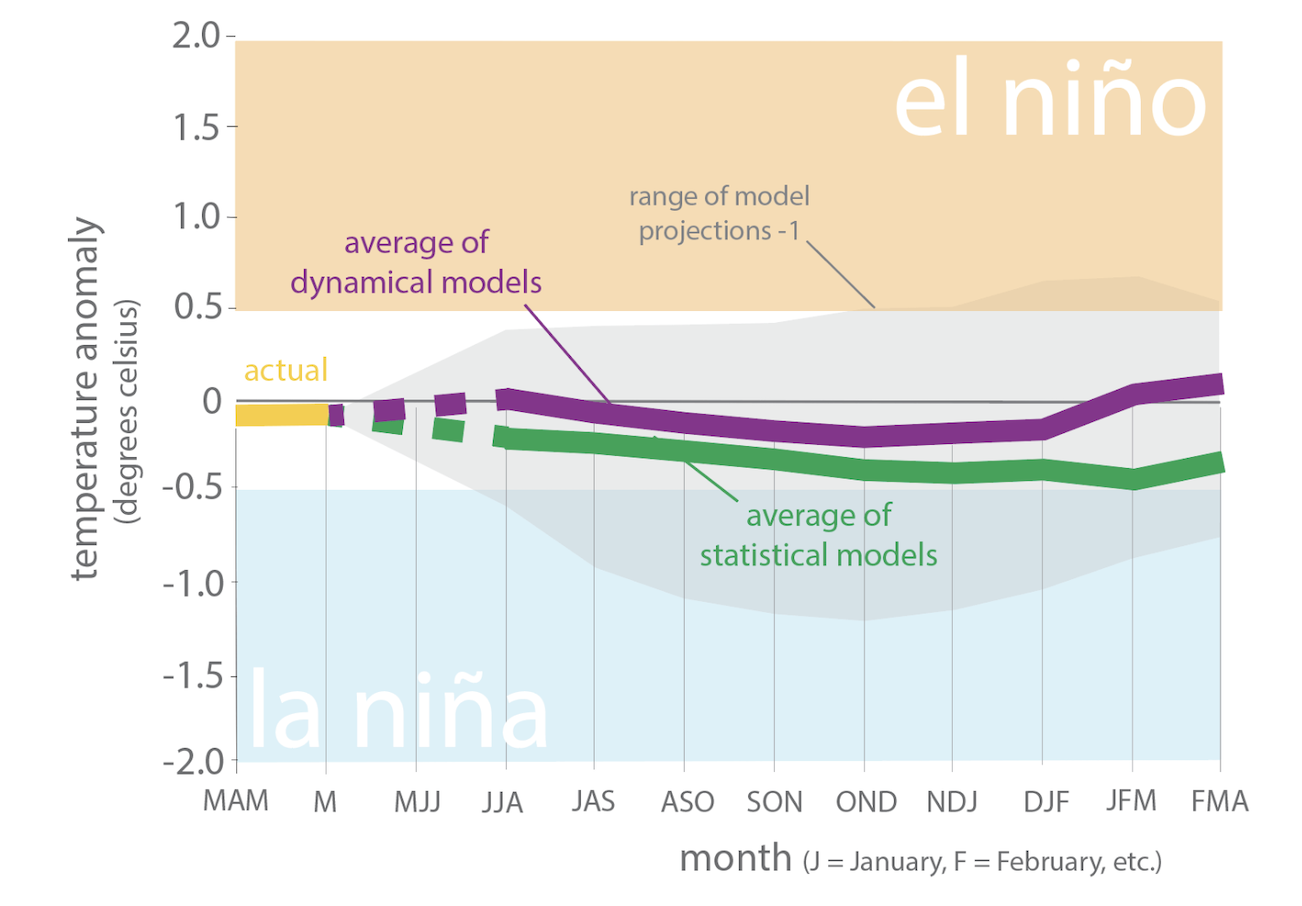

As Texas looks toward the months ahead, the climate picture remains in a neutral zone—what scientists call La Nada. That means we’re experiencing neither El Niño nor La Niña, and current models suggest these neutral conditions will likely continue well into 2026.

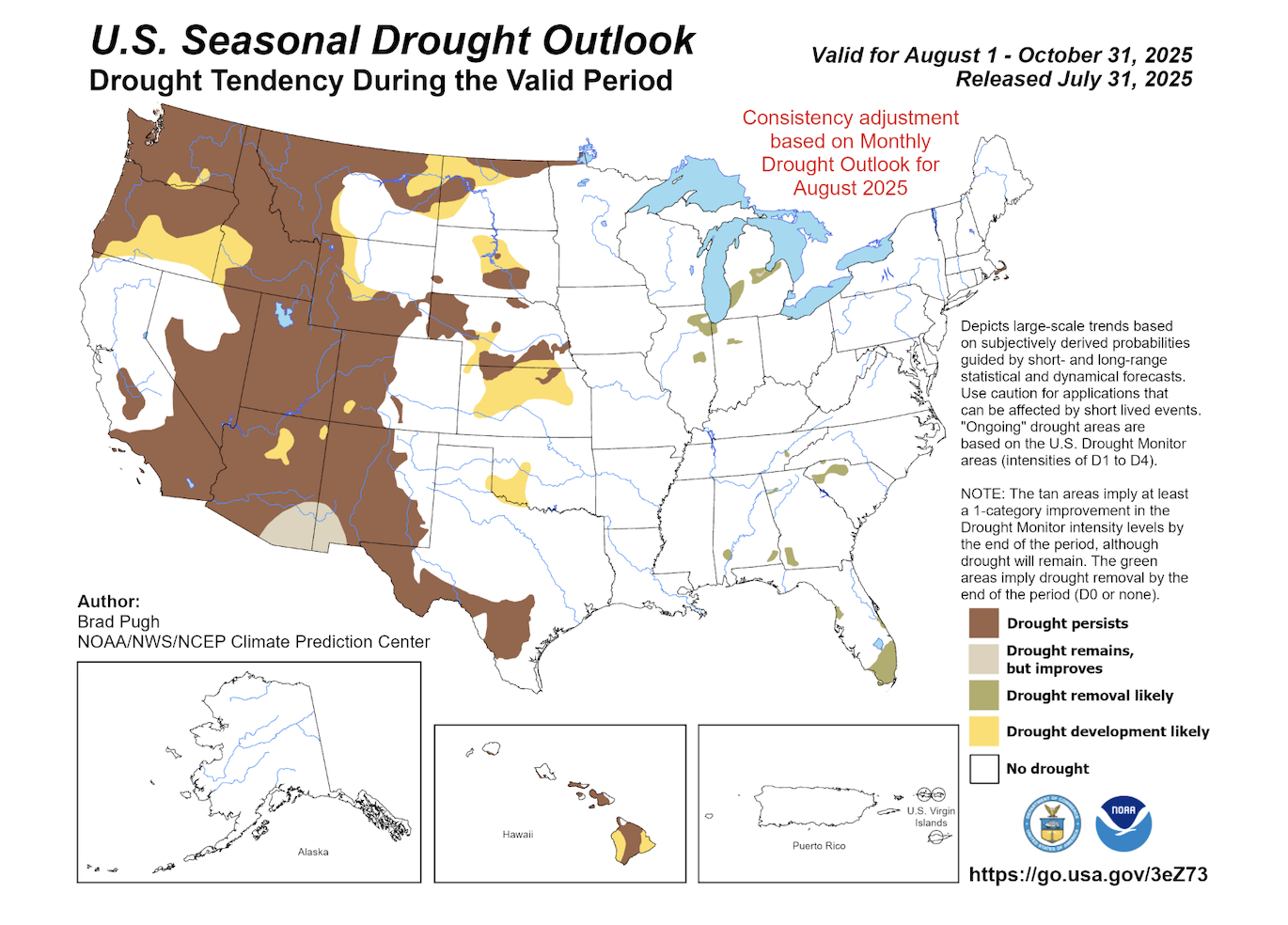

For drought, the outlook through October still points to stubborn challenges. Dry conditions are expected to persist along the Rio Grande and in parts of South-Central Texas, even as other regions see improvement.

And while rainfall totals for the fall are projected to be near average, the real story will be the heat. Forecasts call for above-normal temperatures across the entire state, a reminder that even when drought eases, the strain of extreme heat can continue to weigh heavily on communities, rangeland, and water availability.

For more information be sure to read the full story here –

Mace, R. (2025, August 13). Outlook+Water: Massive rains in the hill country, drought improvement, but the Edwards is still in drought. Texas+Water. https://texaspluswater.wp.txstate.edu/2025/08/12/outlookwater-massive-rains-in-the-hill-country-drought-improvement-but-the-edwards-is-still-in-drought/?utm_source=Texas%2BWater%2BNewsletter&utm_campaign=698fc79914-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2025_08_06_08_24&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_-698fc79914-536101533&mc_cid=698fc79914&mc_eid=23994de06b