As rangeland ecologists and managers, we are quick to produce definitive results after short-term treatments or management strategies. For example, many of our research studies revolve on the same timeline as graduate students. That in rangeland time, is pretty dang short. That’s why this study is so important. It is the first of its kind and it emphasizes just how crucial long-term research is, because what we think is the answer may just be the tip of the iceberg. There are certain rhythms to pick up on, especially after fire. We just need to stick around long enough with it, to find that rhythm.

As rangeland ecologists and managers, we are quick to produce definitive results after short-term treatments or management strategies. For example, many of our research studies revolve on the same timeline as graduate students. That in rangeland time, is pretty dang short. That’s why this study is so important. It is the first of its kind and it emphasizes just how crucial long-term research is, because what we think is the answer may just be the tip of the iceberg. There are certain rhythms to pick up on, especially after fire. We just need to stick around long enough with it, to find that rhythm.

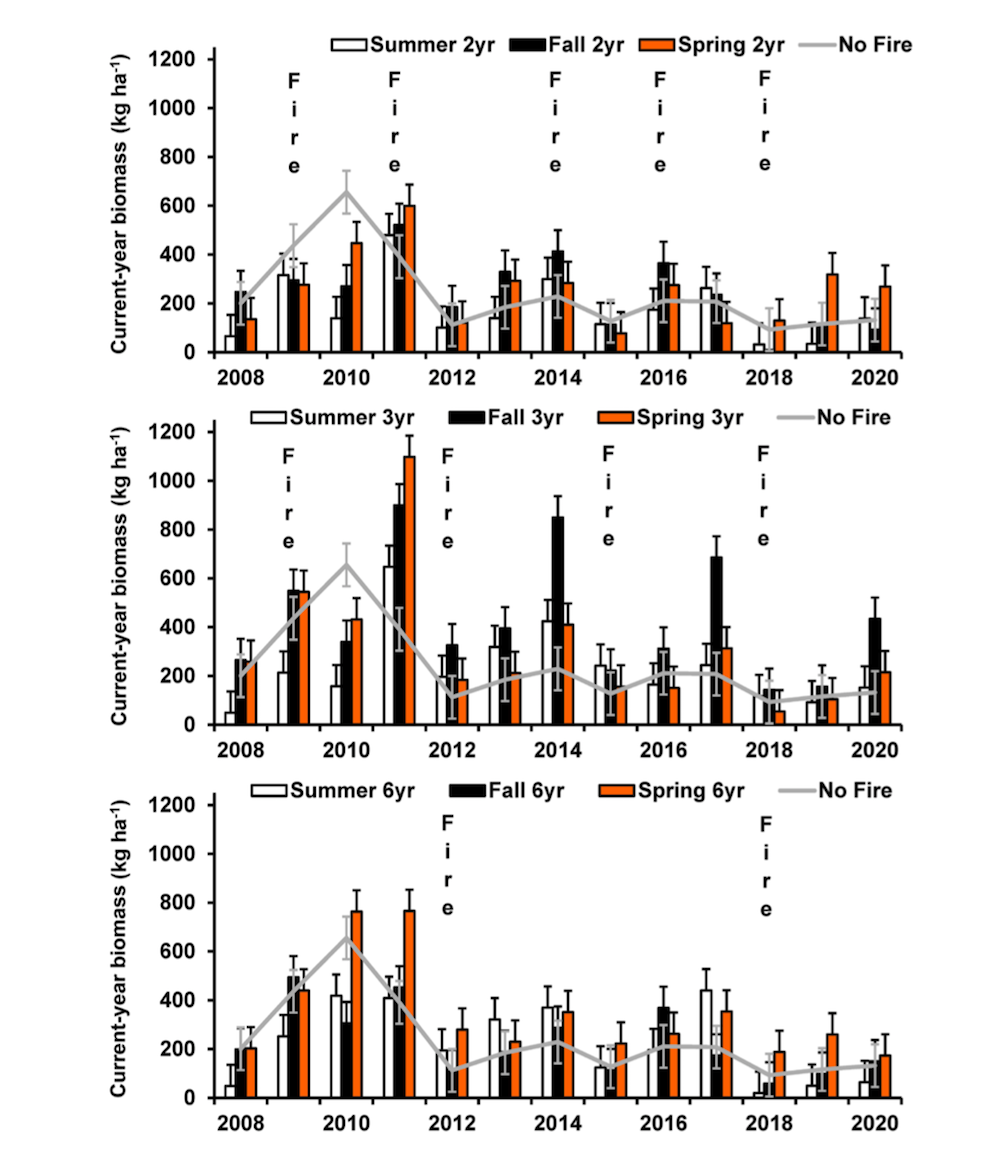

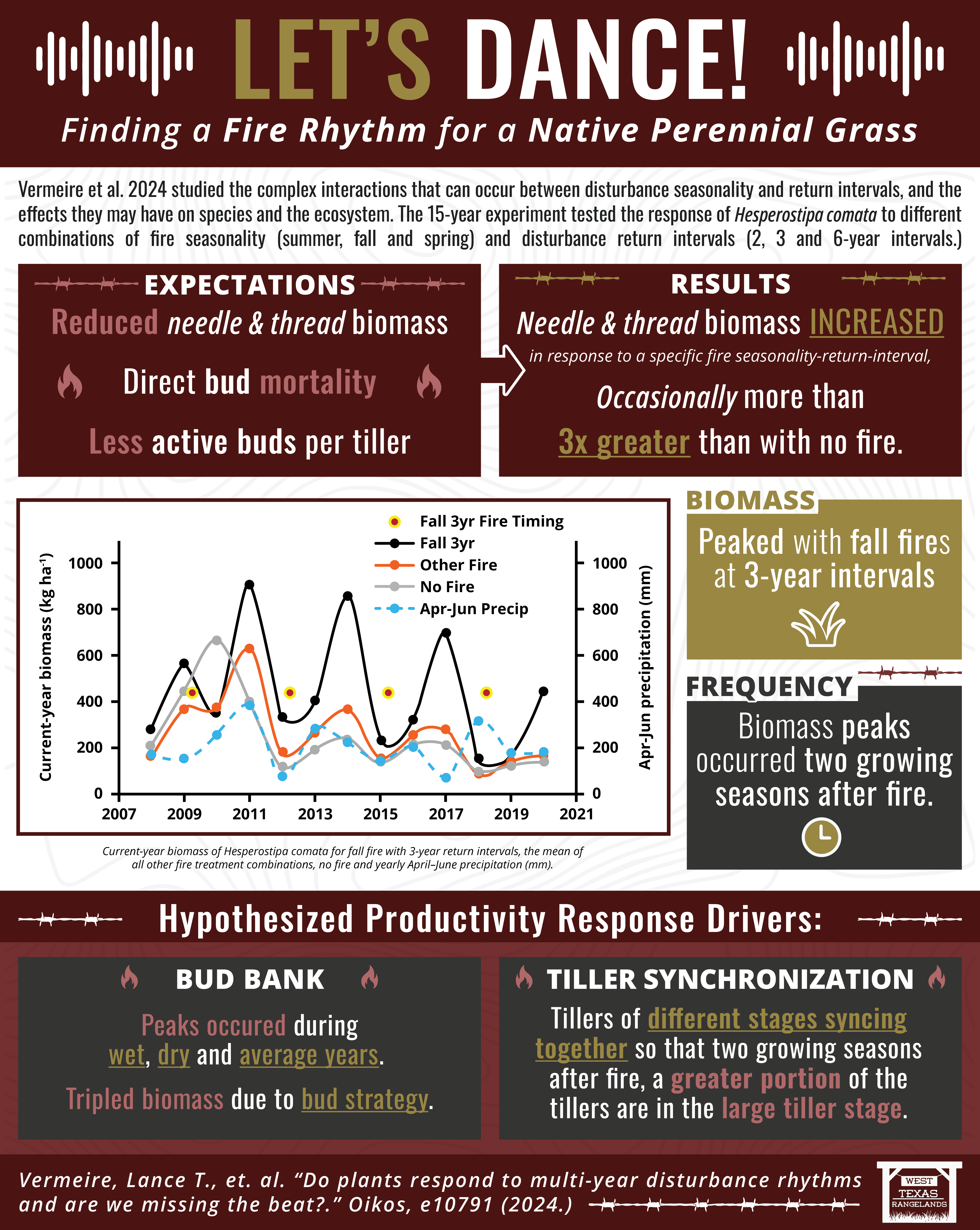

Long-term research studying fire seasonality and return intervals is limited, frankly non-existent. As Dr. Vermeire and team studied unique responses, they inevitably uncovered complex interactions that occurred between seasonality and return intervals on a native, cool-season, perennial grass species commonly found in the Northern Mixed Grass Prairie. This study included a 15-year experiment testing combinations of fire seasonality (summer, fall, spring) and fire return intervals (2,3,6-years).

Due to previous research that was done, it was expected that direct bud mortality would sometimes occur with fire, and that the number of active buds per tiller would be reduced (Russell et al. 2015, 2019). Based on this research for this study, it was hypothesized that biomass could be reduced with repeated fires. Basically, researchers thought that needle-and-thread was a fire sensitive species and it could eventually be pushed out of the plant community with frequent prescribed fires.

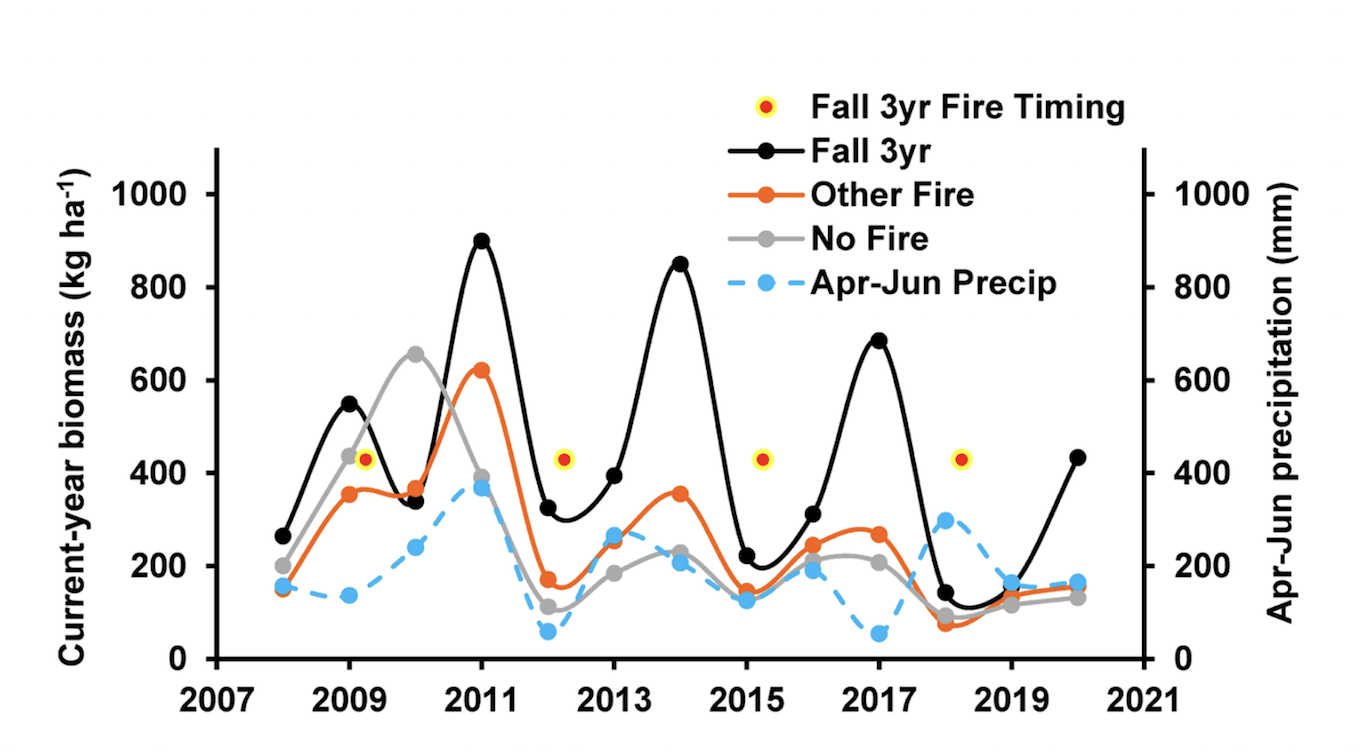

However, fire increased needle-and-thread biomass with a strong, rhythmic response pattern to a specific fire seasonality-return-interval combination (fall fire at 3-year return intervals) that periodically increased biomass to more than three times that with no fire. Through the first four post-fire growing seasons, biomass with summer, fall and spring fire across return intervals was 41, 89 and 93% of that with no fire. Afterward, no fire combination produced less biomass than no fire and recurring patterns emerged with large increases in biomass, particularly with fall fire at 3-year intervals. Peak biomass years were regularly two growing seasons after 3-year fall fire and occurred across wet, near-average and dry conditions.

What was once thought to be a fire sensitive species, just needed to be studied more in order to pick up on the beat that this grass was dancing to fire. The short-term negative effects were reversed and regular patterns only emerged 5 years after the study began! All of this emphasizes the importance in longevity of studying unique fire responses, after multiple fires, across varying conditions. Our grasslands are trying to tell us their recipes and rhythms, we just need to be patient and listen long enough!

Well done Dr. Vermeire and team! You found the beat!

For more information and the full study, be sure to check it out here – Do plants respond to multi-year disturbance rhythms and are we missing the beat?.