The United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit issued an important ruling in Iron Bar Holdings, LLC v. Cape, a case regarding “corner-crossing” on checkerboarded land in the West. This important decision impacts landowners and the public alike.

Background

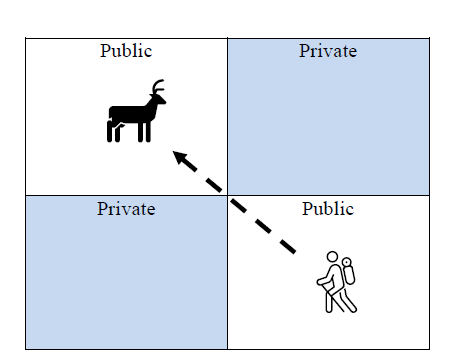

Across the western United States, there are millions of acres platted into squares that alternate in ownership with one square being private and the next public that resembles a checkerboard. For 150 years, a conflict has been brewing over property law and access to public lands in these checkerboarded areas. The court framed the question as follows: “Can a private landowner prevent a person from stepping across adjoining corners of federal public land?” In other words, does a person on public land commit trespass on the adjacent private land when he or she corner-crosses in this manner?

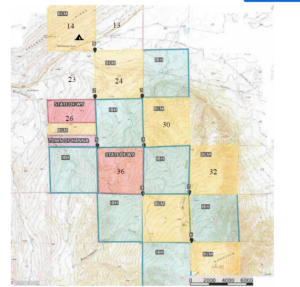

Iron Bar Holdings, LLC (“Iron Bar”) owns a checkerboarded ranch in Wyoming spanning 50 square miles. Their holdings include privately owned land, federal public lands, and state-owned public lands. There are 27 publicly owned parcels, totaling 11,000 acres in this 50 square mile area. The only way to access these state and federal lands (other than by aircraft) is by corner-crossing between Iron Bar’s private holdings. Iron Bar, seeking to prevent corner-crossing, posted two no trespassing signposts connected by chains over the USGS survey marker denoting the corners of several of its sections of land.

The BLM authorizes elk hunting by the public on federal lands in this part of Wyoming. The Defendants are elk hunters from Missouri who traveled to Wyoming to hunt elk in 2020. They intended to access the various squares of public land by corner-crossing over Iron Bar’s property. The hunters used a GPS mapping tool to ascertain land ownership. Using this tool, they were able to “corner-cross,” stepping directly from one piece of public land to the next. They swung themselves around the no trespassing sign posts to cross Iron Bar’s corners without touching their land. They never made contact with the surface of Iron Bar’s land, although they did momentarily occupy its airspace when making their corner-crossing. For several days, the Defendants hunted on public land, Sections 24, 26, 30, and 36 on the map below. The hunters returned in 2021, this time bringing a steel A-frame ladder to corner-cross without even touching Iron Bar’s signposts.

Iron Bar employees confronted the hunters in 2020 and 2021. Employees interfered with hunting activities by driving vehicles across public parcels to scare the elk away. Employees called the sheriff and Wyoming Game and Fish Department, but both refused to take action.

Litigation

In 2021, Iron Bar’s ranch manager called the local prosecutor’s office, and the prosecutor agreed to charge the hunters with criminal trespass. The hunters took this case to a jury trial and were acquitted of the criminal trespass charge.

The same day that the jury found for the hunters in the criminal case, Iron Bar served the hunters with this lawsuit for civil trespassing, claiming $9 million in damages for diminution of property value.

The trial court granted the hunters’ motion for summary judgment, ruling corner-crossing did not constitute unlawful trespass.

Iron Bar appealed.

Tenth Circuit Opinion

The United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit affirmed. [Read Opinion here.]

History

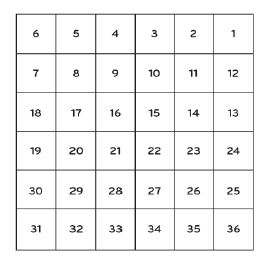

The opinion beings with an interesting history lesson on land ownership and expansion in the American West. The checkerboard approach to land ownership, the court explains, came out of the development of the railroad. It created townships, which were then subdivided into 36 sections (640 acres each), as depicted below. The odd-numbered sections were granted to railroad companies corresponding to each mile of track the company laid. The ownership of even-numbered squares was retained by the federal government.

The first conflicts arose in the 1800s during the range wars between cattlemen and sheep herders, and ranchers against homesteaders. It was the classic open range versus closed range dispute. When cattlemen began to fence land, including the publicly-owned checkerboard squares, Congress stepped in with the Unlawful Inclosures Act of 1885 (UIA).

Airspace Ownership – Wyoming Law

The court turned to the question of whether Iron Bar owns the airspace rights, and the corresponding right to exclude corner-crossers from its airspace. Property rights are defined by state law, and the right to exclude “has long been a core property right.” Under Wyoming law, ownership of the space above land is vested in the surface owner, subject to the right of flight. The law has long held that a trespass may be committed on, beneath, or above the surface. Practical concerns over how this doctrine would square with air travel reached the United States Supreme Court in 1946 in US v. Causby. There, the Court held that a landowner “owns at least as much of the space above the ground as he can occupy or use in connection with the land.” The Court also held that invasions of low-level space are in the same category as surface invasions. In light of this, the right to exclude must apply to at least low-level airspace under Wyoming law.

The Checkerboard – Federal Law

Next, the court turned to how the federal UIA has overridden Wyoming’s civil trespass law in this situation.

The UIA

The UIA makes inclosures of public lands unlawful, and it prohibits the obstruction of free passage or transit over or through public lands. The court rejected Iron Bar’s argument that it did not “inclose” public lands because it did not fence in the land at issue. The court noted that a fence may be one way to create an inclosure, it was not the only way to do so. Non-physical barriers, such as using no trespassing signs, can also be considered an inclosure under the UIA.

Checkerboard Case Law

Next, the court addressed several cases on checkerboarded land:

- Buford v. Houtz: Holding that appropriating public lands is presumptively unlawful.

- Camfield v. United States: Finding UIA was constitutional and government could require landowners to abate fence around public land; definition of inclosure broader than just fences.

- Mackay v. Uinta Dev. Co.: Sheep rancher entitled to reasonable way of passage over uninclosed tract without being guilty of trespass.

- McKelvey v. United States: “Free passage or transit…is to be unobstructed.”

- Leo Sheep Co. v. United States: Government does not have implied easement to build road across land in the checkerboard.

- US ex rel Bergen v. Lawrence: Rancher ordered to remove fence enclosing 15 sections of public land, despite being constructed completely on private land except where it crosses common corners of public land; affirmed UIA still the law; limits holding of Leo Sheep to easement cases; no unconstitutional taking when government abates a nuisance; and law prevents obstruction of free passage or transit for any and all lawful purposes over public lands.

Application

The court explained that although courts have not been entirely consistent in the checkerboard cases, the decision in Bergen makes the application to the instant case straightforward. “A barrier to access, even a civil trespass action, becomes an abatable federal nuisance in the checkerboard when its effect is to inclose public lands by completely preventing access for a lawful purpose.” The court noted that Leo Sheep would likely prevent the hunters from seeing a public road across private land, but that was not the issue here.

The court also noted that the same result would occur even if Iron Bar held grazing leases on the public land. A grazing lease does not convey fee title, and the UIA’s exception for private landowners extends only to those holding fee title.

Lastly, the court held there was no taking of Iron Bar’s property rights. “All that Iron Bar has lost is the right to exclude others…from the public domain–a right it never had.”

What Happens Next?

Iron Bar could decide to appeal this case to the United States Supreme Court.

Interestingly, the Tenth Circuit did note that its decision may leave open questions for landowners and the public alike with regard to the checkerboard. These include issues of who may be liable during a corner-crossing incident, and what duty of care each party owes to each other.

*NOTE: The opinion used the spelling “inclosure” rather than “enclosure.” This blog post adopts the same approach.