Recently, the Ft. Worth Court of Appeals issued a ruling in Berry v. The New Gainesville Livestock Auction, LLC case involving a dispute between a cattle purchaser and a local auction barn who sold him eleven head of cows. This case offers a few important considerations for us to consider.

Photo via Livestock Marketing Association

Background

Berry runs a small cow-calf operation on 40 acres in Cooke County and has done so since 2005 in addition to his full-time job as a CPA. In October 2017, Berry attended a sale at The New Gainesville Livestock Auction (“Auction”) where he was interested in cows with calves by their side or cows bred to calve in the Spring. He purchased eleven cows for $17,325 total.

Two months later, on December 24, 2017, the first cow calved. Six more calved over the next two weeks. Five of the seven calves born survived. Berry testified he continued checking the cows, but the remaining four cows never calved.

Berry sued the Auction for breach of contract and a violation of the Deceptive Trade Practices Act, claiming it misrepresented the cows as being bred to calve in the Spring when they were not.

Trial

Berry was the sole witness for his case. Berry testified that at the Auction, gestation of cows is announced in two ways. First, the auctioneer verbally says the gestation when they enter the sale ring. Second, each cow is marked on the hip with a number indicating how many months bred. He testified that the majority of the eleven cows he bought at the Auction were marked with 4s or 5s, indicating they were 4 or 5 months pregnant. He said he bought the cows because they were going to have calves in April. Berry also testified that the gestation period of a cow varies from 9-12 months. Berry testified at his deposition that the auctioneer stated that the cows were going to “spring in April” and that “they’re heavy springers or whatever.” When questioned about his understanding of the term “heavy springer,” at the trial, Berry said he misspoke using that term in his deposition. He said he understood that a “springer” would calve in the Spring, and a “heavy Springer” was related to the high- or low-birth weight status of the bull to which she was bred.

Berry further testified the four cows never calved. He said he would have seen the calves or evidence that they had calved because he continued to check them. He also testified that he knows two of the cows came into heat immediately because the neighbor’s bull got into his pasture.

Dr. Kinnard, a veterinarian with 45-years of experience who has conducted cattle testing for the Auction since 2008, testified as an expert on behalf of the Auction. He also testified that he palpates the cows and then calls out the months bred. One of his techs writes the number of months down on a chart that is submitted to the Texas Animal Health Commission, and the cow is then paint branded with that number on her hip. With regard to the cows Berry purchased, the records showed those cows were notated as being 5-7 months pregnant. Likewise, the receipt for Berry’s $17,325 payment shows the cows being 5-7 months bred and are identical to the months listed for each cow on Dr. Kinnard’s chart.

While Dr. Kinnard did not recall Berry’s particular cows, he assures clients his estimates will be within 30 days. He also testified that he would not have confused a seven with a three or a four when applying the paint brands to the cows. He testified that they keep the paint branding irons clean, and that it was not possible for a buyer to confuse a 7 as being a 3 or a 4. He also testified that if a buyer did have trouble discerning the paint numbers, he could ask the auctioneer to tell him what the numbers were. Dr. Kinnard stated that “a cow man” would be able to recognize the physical signs of a cow in her last trimester. Berry was the only person to complain about the cows sold at that auction according to Dr. Kinnard.

Finally, Dr. Kinnard also testified that the term “springer” refers to a cow in her last trimester, and has nothing to do with the season of the year in which she will calve. He testified there is “absolutely” a difference between a “cow designated to calve in the spring versus a cow called a springer.” A springer simply designates the physical condition of the cow and state of her pregnancy. A “springer” can calve at any time of the year. Dr. Kinnard testified that a cow’s gestation is 9 months and disagreed that it could ever be 12 months as Berry contended.

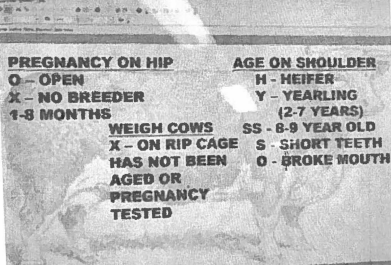

Lastly, James Peyrot, the Auction’s principal owner, testified. He stated that at the Auction’s replacement sales, the majority of cows sold are bred, with the only exception potentially being a young heifer. Open cows are sold on Fridays. Peyrot testified that the auction barn has a large monitor showing the information that would be marked on a cow:

Peyrot also testified that in addition to the markings on the cow, he makes oral announcements about the cows. He testified that Berry’s cows would have come into the ring as a set given that they were so close in age and gestation. He makes his comments regarding age and gestation status based on the paint markings on the cows, rather than the vet sheets. He testified that he did not remember these cows specifically, but he does use the term “springers” or “heavy springer” to mean cows in their last trimester, also called “heavy bred cows.” He testified he well may have said that about Berry’s cows due to their pregnancy status, but would not have represented them as being “spring calvers” as they were too far bred.

Lastly, the Auction raised the question of whether it was possible that the four cows could have calved, but the cows gotten out of Berry’s property, just as the neighbor’s bull was able to get in.

The trial court entered judgment for the Auction, finding that it did not breach its contract with Berry, nor had it committed a false, misleading, or deceptive trade practice (DTPA) or caused injury to Berry. The court awarded the Auction its reasonable attorney’s fees in the amount of $15,563.22.

Berry moved for a new trial and to strike the Auction’s attorney’s fee application. The court denied the motions and Berry appealed the dismissal of his DTPA claim and award of attorney’s fees.

Opinion

The Ft. Worth Court of Appeals affirmed in part and reversed in part. [Read Opinion here.]

First, Berry appealed the trial court’s finding of fact and conclusion of law that Berry failed to prove as a matter of law that Dr. Kinnard’s records or the cows’ painted hip numbers were incorrect. Berry argued the only testimony as to the paint brands was his–that they were 3s and 4s–making this an uncontradicted fact. The Ft. Worth Court of Appeals disagreed. Although Dr. Kinnard and Peyrot did not recall these cows in particular, they testified about usual practices and experience in selling bred cows. Dr. Kinnard’s testimony that he keeps the paint irons clean and would not have used the wrong paint numbers also contradicted Berry’s testimony. Further, the gestation records created a factual issue that the trial court resolved in the Auction’s favor. Further, Berry’s testimony that four cows did not calve, Dr. Kinnard’s records, his testimony that he keeps cattle in groups for sale based on age and gestation, and the possibility that the calves could have gotten off of Berry’s property. Berry also claimed the Auction did not prove the representations made were accurate as they did not have a video or audio recording of the auction. The court rejected this argument–noting it was not the burden of the Auction to show they made truthful representations, but Berry’s burden to prove they made false ones. Thus, the Court of Appeals held that the trial court could reasonably have concluded Berry failed to meet his burden of proving the records or brand numbers were incorrect. The trial court ruling was affirmed.

Second, Berry appealed the award of attorney’s fees to the Auction. Berry claims that the Auction did not plead attorney’s fees, and there was no applicable statute mandating their recovery. The trial court based its award of attorney’s fees on the Auction’s general prayer for relief. However, as the appellate court noted, under Texas law, such a prayer will not support an award of attorney’s fees. They must be specifically pled. Additionally, to recover fees under the DTPA, a defendant must show the plaintiff’s action was groundless in fact or law or brought in bad faith or to harass. The Auction did not prove any of these facts. Further, under Texas Civil Practice and Remedies Code Section 38.001, a party cannot recover attorney’s fees in a breach of contract case unless the party also recovers damages, which the Auction did not do. Absent a statute mandating attorney’s fees, they can only be awarded when supported by pleadings requesting such an award. Because the Auction did not so plead, the award of attorney’s fees was stricken. The portion of the trial court’s opinion was reversed.

Key Takeaways

This case offers a few important considerations.

First, it is a reminder to always pay attention to written records. Here, Berry’s receipt showed that the cows were 5-7 months bred. This notation could have put him on notice that he did not buy cows that would calve in the Spring.

Second, it is really important to ensure one understands any terms of art used in a particular industry. Here, for example, Berry was incorrect in his understanding of the term “heavy Springer.” Regardless of the industry, there are terms like this that are important to understand and investigate.

Third, there is a good reminder about the burden of proof in a lawsuit. Generally speaking, the burden of proving a claim rests with the party making the claim. Here, it was Berry claiming a misleading statement. Thus, it was his burden to prove a misleading statement was made. It was not the burden of the auction to prove they did not do so.

Fourth, let’s look at the issue of recovering attorney’s fees. The general presumption in the law is that win, lose, or draw, everyone gets to pay their own lawyer. That can be changed, primarily by contractual agreement between the parties to allow for attorney’s fees to be recovered in the event of a dispute, or where a statute mandates that fees be awarded under certain circumstances. In order to recover attorney’s fees, however, a party seeking them must expressly request them when filing pleadings in the lawsuit. Failure to do so can, as happened here to the Auction, result in the inability to recover those fees.