The Texas Supreme Court recently upheld the condemnation of a private drive in a case that tested the scope of “public” use under the Texas Constitution and the meaning of Texas Government Code 2206, which prohibits taking private property for certain economic development purposes.

Background

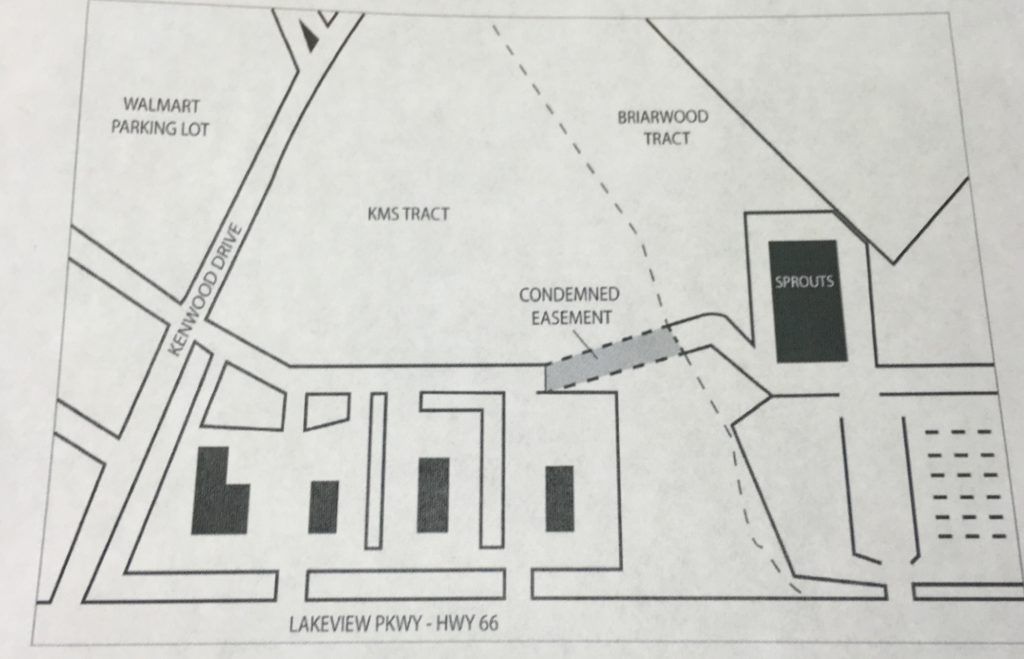

KMS is a commercial real estate developer that owned a 9-acre, triangle-shaped, lot in the City of Rowlett. Four commercial sites were built on the southern boundary of the tract. As part of that development, KMS built a private driveway, allowing access to the four sites from the public Kenwood Drive. The KMS tract is bordered on the east by a tract owned by Briarwood. The private drive did not extend through to the Briarwood property.

In 2012, the City began seeking a high-quality grocery store and eventually identified Sprouts Farmers Market. Sprouts began negotiating with Briarwood for a long-term lease to built a store on the Briarwood tract. The City of Rowlett entered into an economic-incentives deal with Briarwood whereby the City agreed to pay $225,000 if Briarwood would provide access for Sprouts by extending the drive across KMS property to connect with the Sprouts store.

KMS refused to grant an easement to connect its drive with the Briarwood tract, and the parties were unable to agree to terms by which Briarwood could purchase that portion of KMS property. At that point, the City filed condemnation proceedings to condemn the easement that Briarwood was unable to secure through negotiations.

At the special commissioner’s hearing, the Commissioners awarded KMS $31,662 for the taking. At the trial court, KMS moved to dismiss the eminent domain action arguing the taking was not for a “public use” as constitutionally required, and that it violated Texas Government Code Section 2206. KMS also argued that the City’s public use findings were fraudulent, in bad faith, and arbitrary and capricious.

The trial court dismissed KMS’ motion and granted summary judgment to the City. The Dallas Court of Appeals affirmed.

Supreme Court Opinion

The Supreme Court affirmed in a 6-3 decision. [Read opinion here.]

Texas Government Code Section 2206

Initially, the Court held that Section 2206 was inapplicable in this case as the condemnation of the easement was for a transportation project.

After the US Supreme Court decision in Kelo v. City of New London held that the US Constitution was not violated when a city condemned a home as part of an economic-redevelopment plan and turned the land over to a private business, the Texas Legislature enacted Texas Government Code Section 2206. Section 2206 limits the scope of eminent domain powers when economic development and private-party benefits are involved. In particular, the statute provides that a taking is prohibited when: (1) it confers a private benefit on a particular private party through the use of the property; (2) is for public use that is merely a pretext to confer a private benefit on a particular party; (3) is for “economic development purposes”; or (4) is not for a public use. There is, however, an exception to this statute that deems it inapplicable to an entity authorized to take property by eminent domain for transportation projects, including, but not limited to…public roads or highways.

KMS argued that this statute prohibits the taking of the easement, while the City argues the exception applies as the taking here was for a transportation project, namely, a public road. KMS claims the taking was not for a legitimate transportation project and that, instead, the City’s rationale was all pretext for conferring a private benefit on Briarwood and Sprouts.

The Court held in favor of the City, finding that this easement for a road was a transportation project, making the limitations on condemnation in Section 2206 inapplicable.

Necessary for Public Use

Next, the Court held that the City’s exercise of eminent domain in this case was necessary for a public use.

Here, the City argued the condemnation was necessary to provide cross-access, traffic circulation, and emergency vehicle access between retail centers. At oral argument, counsel for KMS admitted that the taking would be for public use, were it not done at Briarwood’s request to obtain a public benefit. The Court stated this may go to the argument of fraudulent action, but it does not support an argument that the taking was not for a public use. Further, KMS did not challenge the benefits of cross-access, traffic circulation, and emergency vehicle access would all be beneficial due to the condemnation of the easement.

Fraudulent

The Court found the condemnation was not fraudulent.

KMS essentially argued that city used eminent domain power to acquire a right for Briarwood that Briarwood couldn’t negotiate for itself. As one amicus brief put it, they alleged that this was a “condemnation for hire.” Although KMS seems to agree that a taking might be proper under different circumstances, it was the City’s ulterior motive to provide an economic benefit to Briarwood and/or Sprouts that was the purpose of this condemnation and constituted fraud.

The Court disagreed, noting that there was discussion of condemnation in emails within the City before Briarwood learned it would not be able to secure an easement on its own. Further, there was no evidence showing that the Sprouts deal would not have closed without the easement. In fact, the store opened without the extended driveway. The Court found that although the City’s economic-incentives agreement with Briarwood may have played a role in the taking, that does not negate any of the City’s justifiable public uses for the easement being necessary. The mere fact that Briarwood and Sprouts might benefit from this taking was not enough to render it improper. To show fraud, KMS needed evidence that “contrary to the ostensible public use, the taking would actually confer only a private benefit.” Here, the Court held, there were plainly public benefits in addition to those private ones for Briarwood and Sprouts. Lastly, the Court noted that although Sprouts and Briarwood could benefit from the cross-traffic, KMS could benefit as well, perhaps more, from the same cross traffic due to the extended drive.

Dissent

Three Justices (Baldock, Lehrmann, and Boyd) dissented. [Read dissent here.]

The dissent focused on the Constitutional Amendment to Article I, Section 17 of the Texas Constitution passed in 2009, after Kelo. That amendment provided limitations on takings when the purpose was to transfer property to a private entity for economic development purposes and requiring that takings be for the public’s ownership, use and enjoyment. This amendment, argued the dissent, changes the “public use” requirement and how it should be analyzed by Texas courts. It is public use–not public purpose–the dissent believes, that should drive the post-2009 analysis of “public use.” Further, the dissent notes that it should be the burden of the City to prove public use, rather than on the landowner to prove the lack thereof.

The dissent would “jettison the superseded precedent, eliminate deference to government declarations of public use, treat condemners like regular plaintiffs, treat property owners like regular defendants, and otherwise normalize standards governing condemnation cases.” Thus, the dissent would remand the case for the lower courts to consider these issues in light of the 2009 Constitutional amendment.

Key Takeaways

First, this case illustrates the extremely deferential position courts generally take with regard to what qualifies as a “public use” under Texas law. Second, the Supreme Court language requires that for a taking to be fraudulent, a party would need to prove that only a private benefit was conferred, which seems a difficult battle at best. Third, this case also illustrates the limited defenses available to a landowner to challenge a taking when it is deemed to be a public use, namely fraud, bad faith, and arbitrariness. Thus, although landowners may challenge the condemning entity’s determination of public use, they face an uphill battle in doing so. Finally, this opinion limits the scope of Government Code Section 2206 by taking a broad approach to defining the term “transportation project” to include a private drive, rather than a roadway or highway.