**This article is not a substitute for the advice of an attorney.**

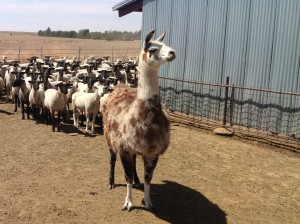

In November, the Illinois Court of Appeals granted summary judgment for defendants in a case involving a llama who attacked a high school student hired by the llama’s owners to work on their farm. The result likely would have been different under Texas or New Mexico law.

Background

The plaintiff was hired by the defendants to work on their pet store and family farm. Even after his employment ended, the plaintiff still periodically cared for the farm animals and cleaned the barns when the defendants were out of town.

The plaintiff claims that a male llama, Beau, frequently caused problems while he was working for the defendants, including hitting him in the face, pushing him into the barn, and charging at him. The plaintiff claimed that the defendants were aware of these incidents, which the defendants denied. On July 6, 2008, the plaintiff came to the farm to care for the animals while the defendants were out of town. He had been told that Beau was not confined to a stall, but left free to roam, and saw the llama in the barn as he began his work. Shortly thereafter, the plaintiff was attacked by Beau and thrown over a fence resulting in a dislocated shoulder.

Lawsuit

The plaintiff sued claiming that the defendants were negligent. The defendants raised the affirmative defense of assumption of the risk, which they claimed barred the plaintiff from recovering. The trial court granted summary judgment in favor of the defendants, finding that the plaintiff assumed the risk of injury. Recently, the Illinois Court of Appeals affirmed.

Under Illinois law, assumption of the risk occurs when a plaintiff “has implicitly consented to encounter an inherent and known risk, thereby excusing another from a legal duty which would otherwise exist.” This defense is based on the idea that “a plaintiff will not be heard to complain of a risk which he has encountered voluntarily, or brought upon himself with full knowledge and appreciation of the danger.”

The court reasoned that because the plaintiff had been attacked by the llama in the past, knew that the llama was free to roam at the time of the incident, and saw the llama in the barn while he was working, he assumed the risk and the defendants were not liable. In light of this, the court granted summary judgment in favor of the defendants and the case will not be heard by a jury. It remains to be seen whether the plaintiff will seek review from the Illinois Supreme Court.

[The opinion can be found at Edwards v. Lombardi, 2013 Ill. App. LEXIS 806 (Ill. Ct. App. Nov. 20, 2013).]

Texas Law

It is important to note that Texas no longer recognizes the doctrine of implied assumption of the risk as a defense to negligence cases. In Texas, only express assumption of the risk–meaning that the plaintiff orally or in writing expressly consented to the risk at issue–is recognized as a defense. See Farley v. MM Cattle Co., 529 S.W.2d 751, 758 (Texas 1975). Instead of recognizing implied assumption of the risk, Texas allows for comparative negligence and a jury is allowed to apportion fault between the plaintiff and defendant. Thus, were the llama case to have occurred in Texas, summary judgment likely would not have been granted. Instead, the case likely would have been sent to a jury that would have compared the fault of the plaintiff to the fault of the defendants and assigned percentages to each. The plaintiff’s recovery would have been reduced proportionally based upon the level of fault assigned. For example, if the plaintiff’s medical bills were $10,000 and he was found to be 50% responsible, then he would only be allowed to recover $5,000 from the defendants. If a plaintiff is found more than 50% responsible, he is barred from recovery. See TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE 33.001.

New Mexico Law

New Mexico, too, has abrogated the implied assumption of the risk doctrine, replacing it instead with comparative negligence. See Scott v. Rizzo, 96 N.M. 682, 634 P.2d 1234 (1981). Under New Mexico law, however, there is no provision as in Texas that bars recovery if the plaintiff is over 50% at fault. Instead, the recovery is reduced by the amount of the plaintiff’s determined fault, regardless of that percentage. For example, if a plaintiff’s medical bills were $10,000 and he was found 70% responsible, he would be allowed to recover $3,000 under New Mexico law. Thus, like Texas, the were the llama case filed in New Mexico, it is unlikely that summary judgment would have been granted and, instead, the jury would have been allowed to hear the evidence and apportion fault.