Bayou Geography and Watershed Boundaries

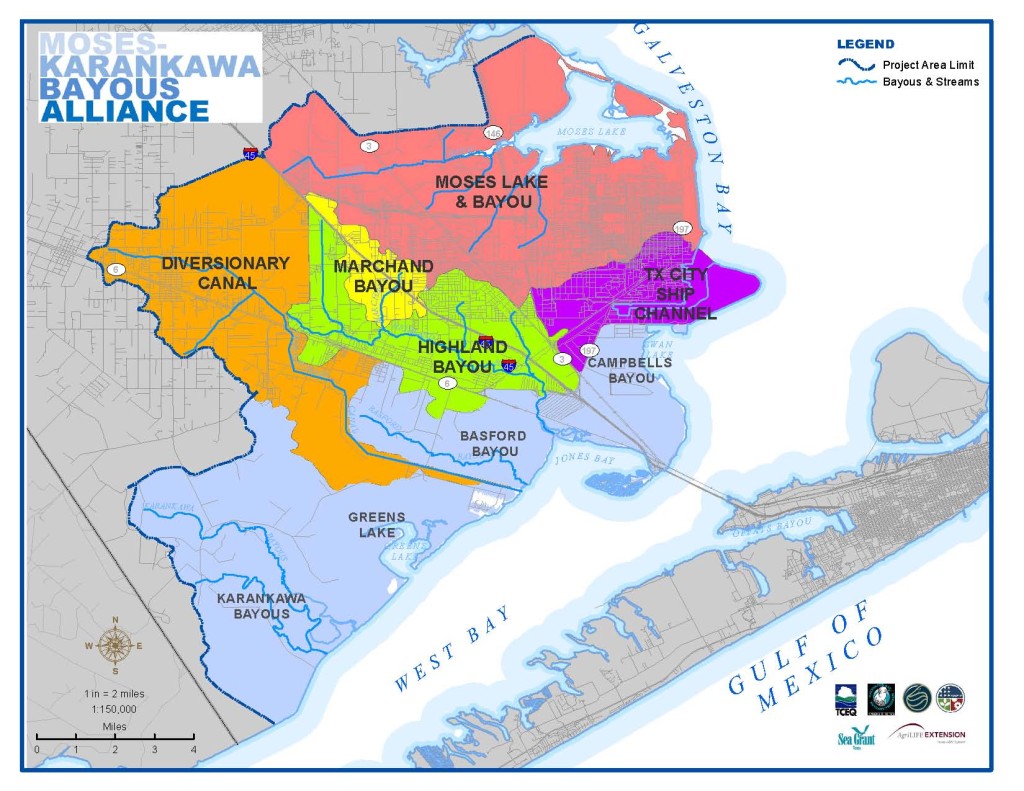

The Highland Bayou Coastal Basin is a 120 square mile drainage basin located on mainland Galveston County. Bayou and stream segments in the study area consist of non-tidal, tidally influenced, and tidal waters. Land in the study area is a mix of developed and undeveloped lands, including agricultural lands, prairies, wetlands and estuaries. Alterations to the natural drainage of the bayous since western settlement have had a defining effect on drainage in the study area. Significant alterations include channel fills and cuts, levees, and wetland infill. The Galveston Bay Estuary system into which the bayous drain is one of the largest estuaries along the American coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

Defined watersheds in the basin are Highland and Marchand Bayous, Moses Bayou and Lake, The Texas City Ship Channel, the Diversionary Canal, and the estuarial bayous of Campbell, Basford, Greens Lake, and Karankawa (alternatively spelled, Carancahuah). Highland and Marchand Bayous are the priority study areas in the project area.

Historically, Highland Bayou’s headwaters were in Santa Fe, Texas and ran a course of approximately twelve miles into Jones Bay and then into West Bay. Today, the Diversionary Canal intercepts these headwaters in Santa Fe and directs the flow into a canal that drains directly into West Bay at a point one and one-half miles south of Highland Bayou’s natural outlet.

The topography of the basin is flat, rising from sea level to an elevation of 24 feet in and around the City of Santa Fe. Highland and Marchand Bayous originate as freshwater bayous before transitioning to estuarine conditions. Fresh water in the bayous is largely precipitation-driven overland flows. During extended periods of little or no precipitation, flows in the bayou are observed to be stagnant or determined by tidal influence. Fresh water provided by municipal systems and groundwater wells eventually is discharged into the drainages of the bayous system.

Overland flows drain areas of development and areas of natural cover. Large portions of the study area are intensely developed. Significant areas are undeveloped, yet are disturbed from their native condition. Overland flow from developed areas are likely to carry more non-point source pollutants and have ‘flashier’ flow rates following a precipitation event than natural terrain.

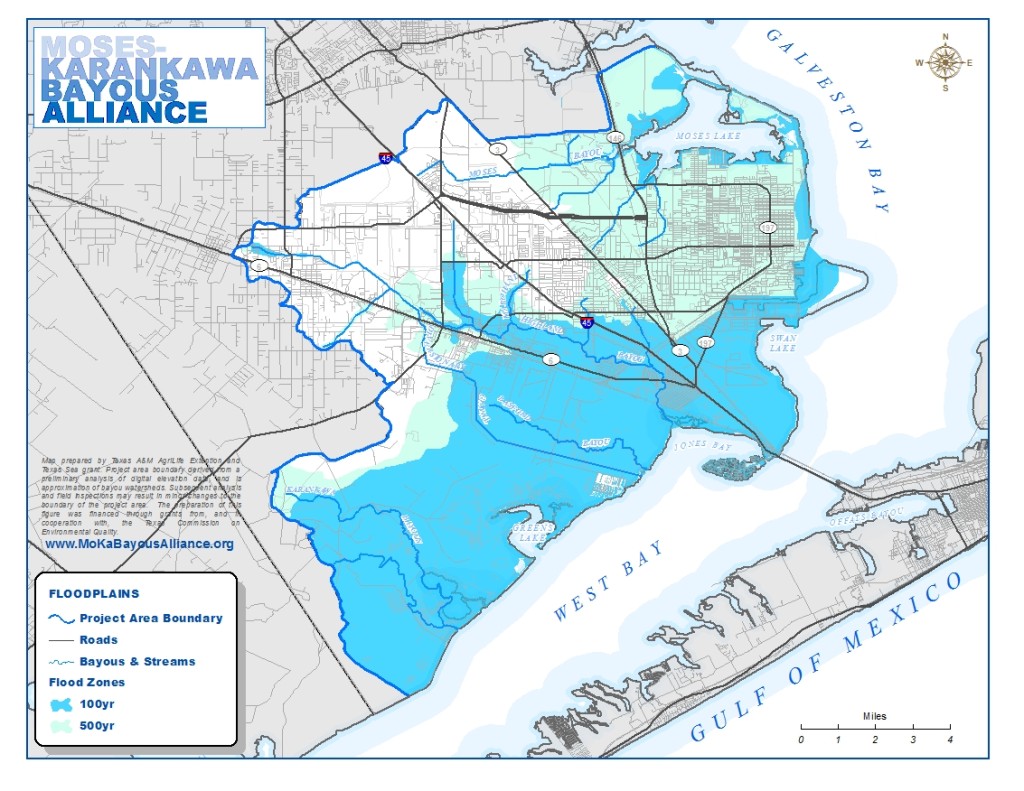

The sea-level elevation and flat topography of the coastal basin make the study area vulnerable to flooding from runoff. The tributaries of Highland Bayou headwaters have been altered for flood management through channel straightening and widening, a responsibility of the Drainage Districts in Galveston County. The 100 year flood zone extends beyond Highland Bayou’s banks to encompass developed areas of Hitchcock, Bayou Vista and La Marque. Most of Highland Bayou’s natural course is situated within the surge zone of a Category 1 Hurricane, designating the area as highly vulnerable to storm surges from approaching tropical cyclones. Tidal flooding frequently impacts the lower segments of the Highland Bayou watershed, even from prolonged non-tropical storm events.

Ecosystem

The Highland Bayou study area is situated in the ‘Gulf Coast Prairies and Marshes’ ecoregion of Texas. The study area’s edge location with neighboring ecoregions means that there is a diverse array of species and habitats caused by the mixing of habitats between ecoregions. Habitats in the study area include marshes, wetlands, prairies, and woodlands. Development over the last hundred years–accelerating in the last couple of decades–has resulted in the loss of significant areas of habitat. Still there are areas of prime habitat types, held by both private and public entities.

The natural habitats of greatest significance to the Highland Bayou study area and for the Bay system are the tidal marshes and wetlands. The amount and variety of life supported by these systems are thought to be among the most productive ecosystems in the world. The marshes also support species at some point in their life cycle that are of significance to commercial and recreational fishing.

The study area is home to the following habitats:

- Coastal Prairie and Grassland: The coastal prairie ecosystem of Texas and Louisiana is one of the most critically threatened in the world. Remaining coastal prairie parcels are highly fragmented and still severely threatened by encroaching development and invasive, non-native species. Today, there are several areas of prime coastal prairie habitat in the study area, including points south of Hitchcock and the Texas City Prairie Preserve, north of north of Moses Lake (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Geological Survey, 1999). Another area of native grassland is the former Camp Wallace military base, now managed by the University of Houston system, and is located west of FM2004 between Hitchcock and US I-45.

- Estuarine and Tidal Fringe Wetlands: These wetlands can be vegetated wetlands or as open tidal flats. Thickets of marsh grasses allow small marine life to shelter there from predators. Some marine species will spawn and grow in the marshes before migrating to open waters. Natural openings in the grasses also allow for colonies of birdlife that forage the marshes for food. Tidal marshes line Highland Bayou from Pierce Marsh (west side of Jones Bay) and Virginia Point up to Mahon Park in La Marque. The marshes expand landward from the bayou for several hundred feet to several miles. Significant tidal marshes also exist around Moses Lake.

- Riparian forests, forested wetlands, and Coastal Flatwoods: Woodlands occur naturally in the study area. Riparian forests are situated along the banks and floodways of Highland Bayou. Trees and vegetation overhanging the banks of the bayou stabilize these banks, and provide shade and habitat for species that live near the bayou. Forested conditions are known to enhance the flood capacity of watersheds, absorbing and holding rainfall before releasing it slowly over days and weeks back into watershed drainages.

Animal Species of Significance

Estuaries support a diverse range of flora and fauna, terrestrial and marine. The range of habitats, water conditions, and plant life provide conditions that support a diversity of species. Some of these species support the local seafood economy, providing food locally and for export. Other species are important for recreational fishing. Some of the species that can be found in the study area include:

- Eastern Oysters

- Shrimp

- Blue Crabs

- Spotted Sea Trout

- for red fish

- Flounder

- Speckled trout

Colonial Birds

The Texas coast serves as a major nesting area for colonial waterbirds. Common wading birds observed in the study area are the great blue heron, great egret, snowy egret, tricolor heron, little blue heron, ibises, and roseate spoonbills. Open water birds include royal terns, Caspian tern, least terns, sandwich terns, and neotropic cormorants. Up to 139 species have been identified in the Galveston Bay system.

Feeding habitat is likely the determining factor for trends in colonial waterbirds, resulting from the loss of marshlands. Decreases in the quality of the food sources, pollution, increases in death through disease, and loss of nesting habitat also factor into trends for waterbirds. Nesting sites are susceptible to a number of threats. Human disturbances, particularly during nesting season, can disrupt breeding cycles and stress hatchlings. Colonies can be lost through erosion, subsidence and habitat conversion like dredging and infill. Predation by terrestrial animals and red fire ants are also known threats.

Endangered and Threatened Species

There are a number of species in the study area that are federally recognized as endangered or threatened. The state of Texas also maintains an endangered species list and some of the species below may or may not be on the federal list but all can be found on the state’s list of endangered and threatened species. The following species have been known to inhabit and migrate in and around the general project area. Certain species have not been observed in the study area region for decades.

Birds

- The Attwater’s greater prairie chicken

- Eskimo curlew

- Piping plover

- Sprague’s pipit

- Reddish egret

- White faced ibis

- Wood storks

- White-tailed hawk

- American peregrine falcon, Arctic peregrine falcon, peregrine falcon

- Bald eagle

- Brown pelican

- Whooping cranes

Fish

- Smalltooth sawfish

Mammals

- Red Wolf

- West Indian Manatees

- Louisiana Black Bear

- Plains spotted skunks

Reptiles and Amphibians

- Loggerhead sea turtle

- Atlantic Hawksbill sea turtle

- Kemp Ridley’s sea turtle

- Green sea turtle

- Leatherback sea turtle

- Alligator snapping turtle

- Texas diamondback terrapin

- Texas horned lizard

- Timber/canebrake rattlesnake

- Gulf saltmarsh snake

Human Impact

Significant residential development has also been permitted on estuary lands, notably the communities of Bayou Vista, Tiki Island, and Harbor Place. Development on these estuaries results in the hardening of shorelines through constructed bulwarks and embankments. This results in the loss of intertidal habitat. U.S. Interstate-45 and the Texas City Levee system also restrict natural tidal flow across the Virginia Point Estuary and the Highland Bayou tidal flats between the Texas City rail spur and the neighborhood of Omega Bay.

Tides in the Gulf of Mexico have a range of three feet. The tides are weakened as they enter the Bay system, and tide ranges vary across the Bay. Tidal flows in the Bay have been altered from their natural circulation patterns by shipping channels and dikes. In particular, the Texas City Dike is understood to deflect circulation away from West Bay, into which Marchand and Highland Bayous drain.

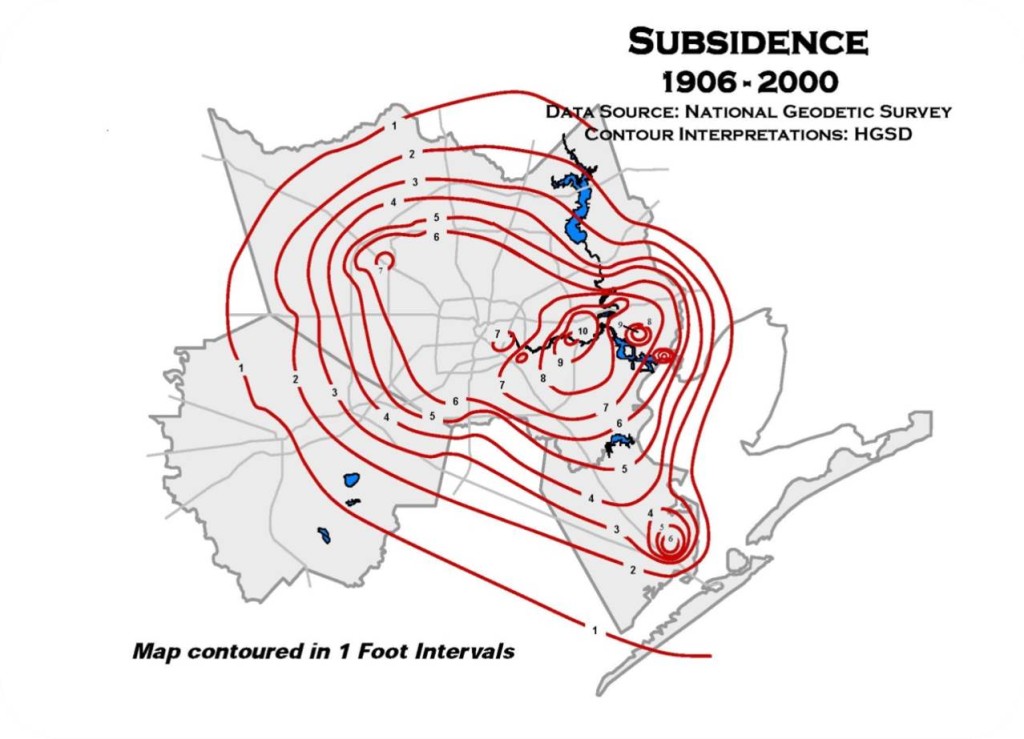

Subsidence occurs naturally in estuarine systems such as Galveston Bay. In the Highland Bayou coastal basin, subsidence has been greatly accelerated through drawdowns of ground water in the study area. Subsidence could also be accelerated through oil and gas extraction. The drawdown of ground water has resulted in subsidence of one to six feet across the study area between the years 1906 and 2000. Groundwater makes up nearly a third of the Houston Region’s water supply. . Since the creation by the Texas State Legislature of the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District in 1975, groundwater withdrawals have been regulated and the rate of subsidence has dropped dramatically around the Bay and in the study area (Harris Galveston Subsidence Districts, 2011).