Cotton harvest on Oct. 20, 2021. (Courtney Sacco/Texas A&M AgriLife Marketing and Communications)

It’s almost time for producers to begin harvesting cotton in this part of the state. Today, we look at the decision to harvest low-yielding fields and discuss the costs and benefits of doing so. We also present a tool to help producers evaluate the profitability of harvesting cotton from low-yielding fields.

Should You Harvest That Field?

As an economic decision, the question of whether to harvest a field is not complicated. A field should only be harvested if the revenue it produces is greater than the harvest cost. The challenge is to identify the correct costs to consider.

Producers should consider any costs associated with planting and growing a crop as sunk costs at harvest time. These costs have been incurred and are not recoverable, so they should not influence the harvest decision. Producers should also ignore any fixed costs associated with harvesting equipment, such as depreciation and interest payments on loans. These costs must be paid and do not change, even if nothing is harvested.

The harvest decision, therefore, should focus on the variable costs associated with harvesting a field. The extension enterprise budgets for cotton in Districts 1 and 2 identify three such costs. These are stripping and module building, ginning, and harvest aid applications. If the revenue produced by a field is greater than the sum of these costs, it makes economic sense to harvest the field.

A Tool to Help with the Decision

To help producers evaluate harvest profitability, economists with Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service have created a harvest decision budget tool. The tool itself is a spreadsheet that calculates the revenue, harvest cost, and net income from harvesting a field.

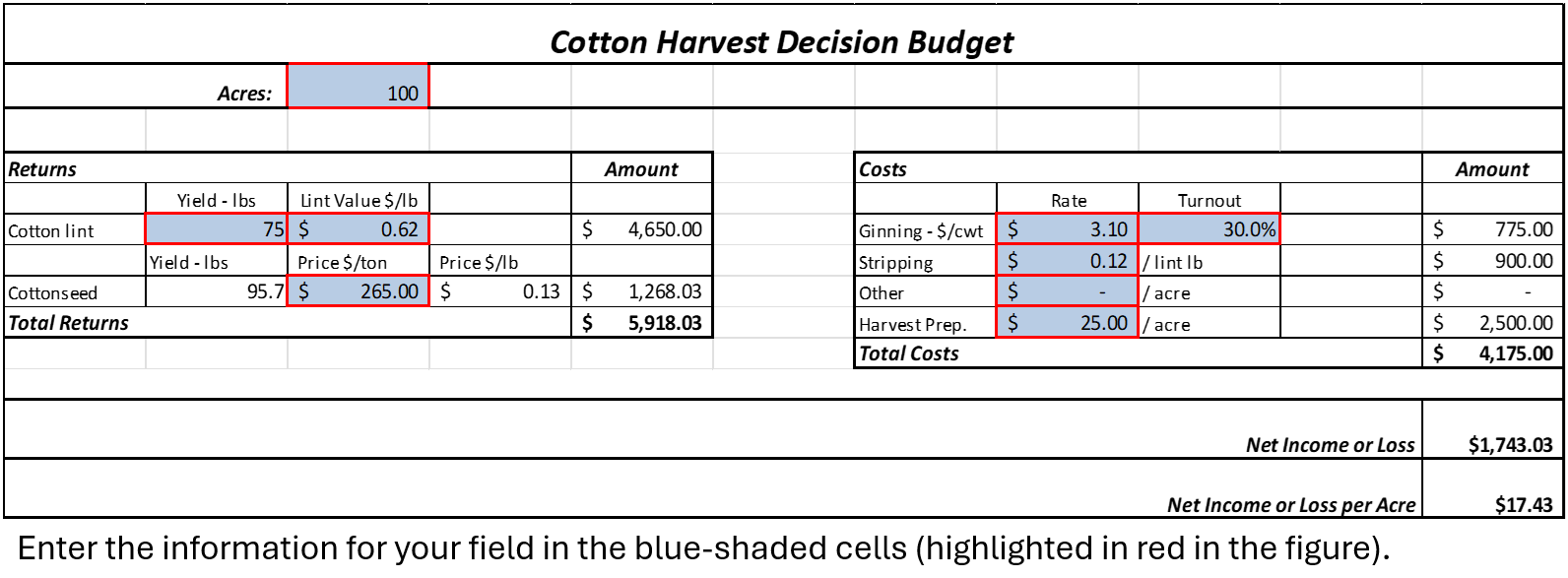

To use the tool, a producer inputs information into the blue shaded cells in the spreadsheet. For example, suppose I have 100 acres of cotton that will only yield 75 pounds of cotton lint per acre. Furthermore, I have the following expectations about the cotton price at harvest and harvest costs:

- I expect a cotton lint price of $0.62 per pound and a cotton seed price of $265 per ton.

- I expect to pay $3.10 per CWT in ginning costs.

- My stripping cost is $0.12 per pound of cotton lint.

- My harvest aid application cost is $25.00 per acre.

I enter all this information in the spreadsheet, as shown in Figure 1. According to the tool, I expect to earn a net income of $1,743.03, or $17.43 per acre, if I harvest these 100 acres. Therefore, I should consider harvesting this field.

Figure 1. Cotton Harvest Decision Budget Example

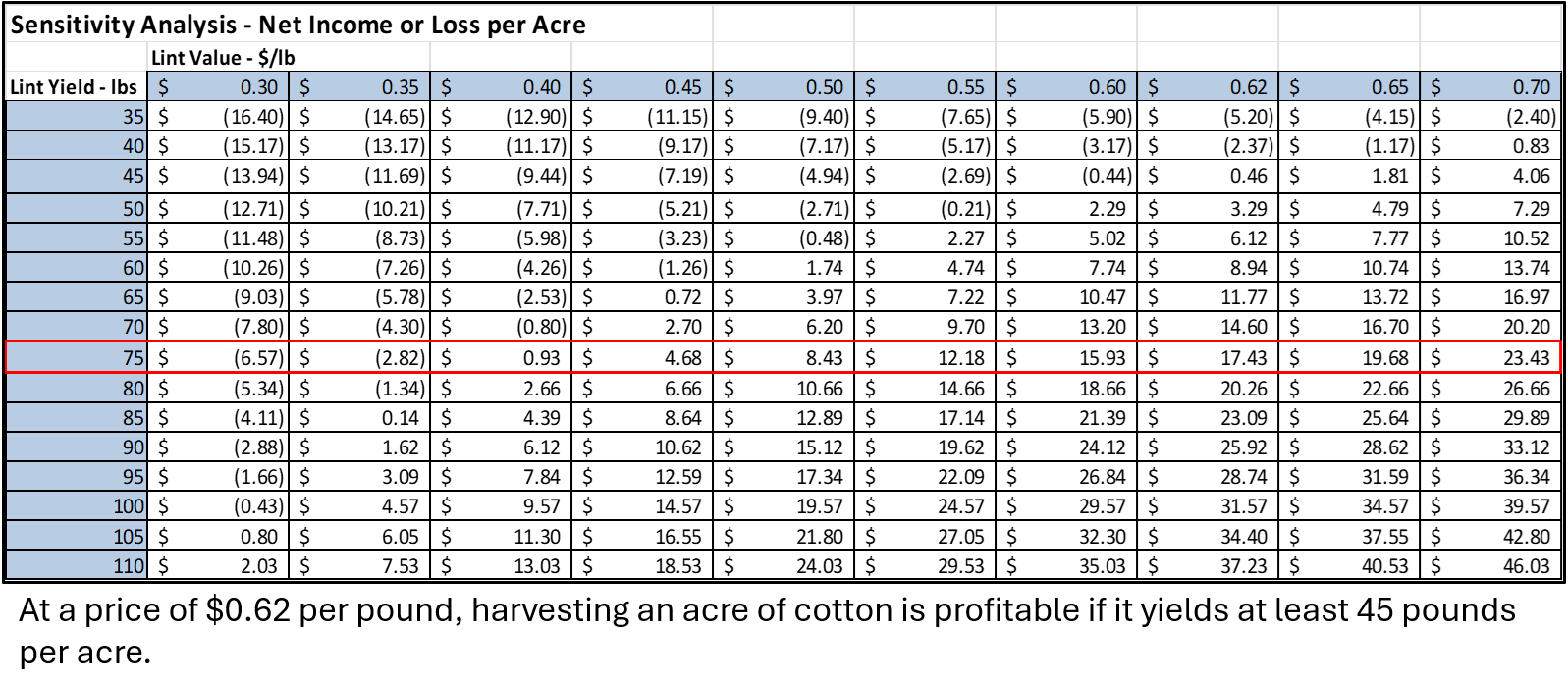

At what price would it not make sense to harvest this field, given its expected yield? Or, at what yield would it no longer be profitable to harvest, given the expected price? To answer this question, the tool performs sensitivity analysis using the harvest cost information provided by the user.

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate this. Both figures show the table that the tool uses to perform this analysis. The numbers in the blue-shaded cells along the top of the table show different potential cotton lint prices. The numbers in the blue-shaded cells along the table’s left-hand side show potential yield values. The numbers in the white-shaded cells report expected net income or loss at different price and yield combinations. Note that you can change the values in the blue-shaded cells to evaluate the profitability of different ranges of prices and yields.

In our example, at $0.62/pound it is profitable to harvest at yields as low as 45 pounds per acre (Figure 2). At 75 pounds/acre, it is profitable to harvest at prices as low as $0.40/pound (Figure 3). Note that as harvest costs change, the net income or loss per acre in this table will also change.

Figure 2. Sensitivity Analysis Example Using the Lint Value

Some Final Thoughts

As you use this tool, keep two things in mind. First, be realistic about the quality of the cotton you harvest from low-yielding fields and the price you can expect to receive for this cotton. If the cotton in these fields is of low quality, you will most likely receive a discount on the price when you sell it. Make sure to account for that price discount as you use this tool. Second, remember that this budget only accounts for the cash costs associated with harvest. Your time and effort have value, and once you account for that value, you may find that harvesting low-yielding fields is not worth your time, even if this tool predicts a positive net income.