by Dr. Tom Isakeit, Extension Plant Pathology; Dr. Gaylon Morgan, Extension Cotton Agronomist

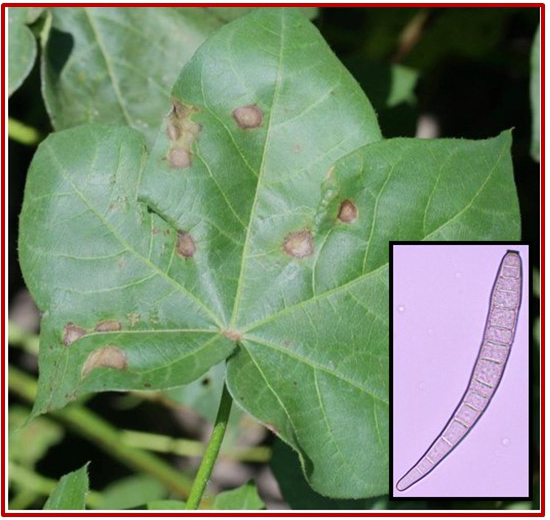

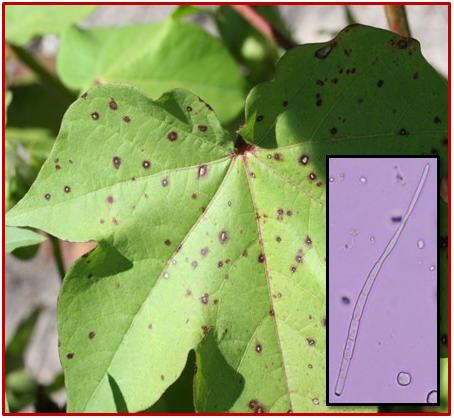

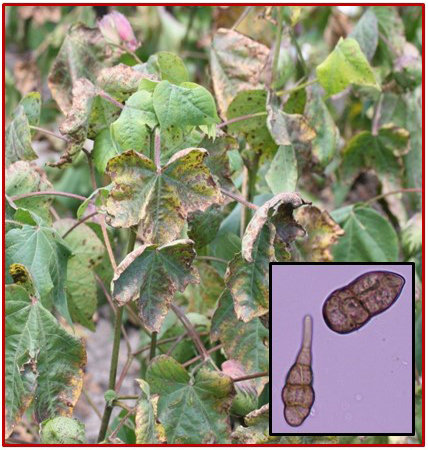

Cotton fields in Upper Coast counties of Texas that are experiencing browning or bronzing of the foliage (Figure 1), often accompanied by defoliation, usually have leaf spots. There can be several different species of fungi associated with these leaf spots. These are species of the genera Corynespora (Figure 2), Cercospora (Figure 3), Alternaria and Stemphyllium (Figure 4). Some fields have leaf spots associated with one species only, while several species may be present in other fields. It’s been my opinion that non-pathogenic stresses are the predominant problem in these fields and that the fungal leaf spots are a secondary problem. An example of such a stress is potassium deficiency, which is confirmed by tissue or soil tests. Often, there are interactions with fluctuating moisture and boll load. Although leaf spots can be found on otherwise normal-looking leaves, they generally are found on senescing leaves or leaves showing the other stress symptoms. My hypothesis is that the fungi are growing on leaf tissue weakened by the other, non-pathogenic stresses. The fungi are probably hastening the defoliation, but I do not think that they are the main factor in defoliation.

In other states like Alabama and Georgia, fungi like Corynespora cassiicola, which causes target spot disease, can be pathogens by themselves. Extensive leaf spots on a leaf can lead to early defoliation. Disease development is associated with frequent rain and yield losses can be significant. Reduction in defoliation has been possible with the timely application of fungicides. It’s my hypothesis that application of fungicides to control fungal spots will not protect yield where the initial culprit is also a major, non-pathogenic stress, as we are seeing in the Upper Coast counties. Currently, I have tests in the Upper Coast and there are also grower trials that may indicate whether fungicides can delay or reduce defoliation.

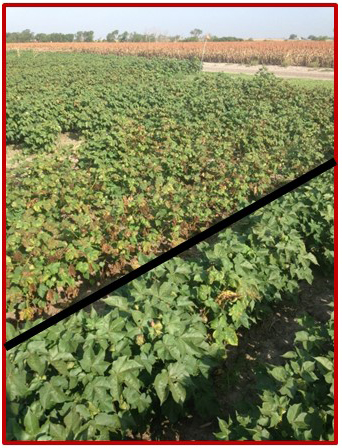

Similar mid to late season nutrient deficiencies have occurred in years past, and is usually a combination of numerous factors contributing to insufficient nutrient uptake to meet the boll demand, including potassium. These contributing factors include the soil potassium levels, the size of the root system, and boll load. Adequate soil potassium levels but a small root system can lead to reduced potassium uptake, which can lead to deficiencies. Potassium, phosphorous, and nitrogen are mobile within plants and are transported to the parts of the plants with the most demand. In a crop with heavy boll load, these mobile nutrients will be translocated from the leaves to the developing bolls and causes nutrient deficiencies in the leaves (Figure 5) and can lead to secondary pathogen infections (Figure 6) and discussed above.

What can be done now to remediate the problem? In fields with a moderate to high level of potassium deficiency symptoms, there really is nothing that can be done at this point. In fields with plants just beginning to show symptoms, multiple foliar applications of potassium may help elevate some deficiency symptoms, but the impact on yield has been inconsistent in previous research trials.

What should be done to minimize the nutrient deficiency symptoms in the future? The most important thing is to collect a soil sample and have it analyzed to determine if adequate potassium is plant available in the soil. Based on some deep soil samples collected in the Upper Gulf Coast region, some fields are substantially lower potassium levels with depth (6-24 inches). This depletion of potassium with soil depth and higher yielding/faster fruiting varieties are the most likely reason for a significant increase in potassium deficiencies showing-up in cotton over the past decade.

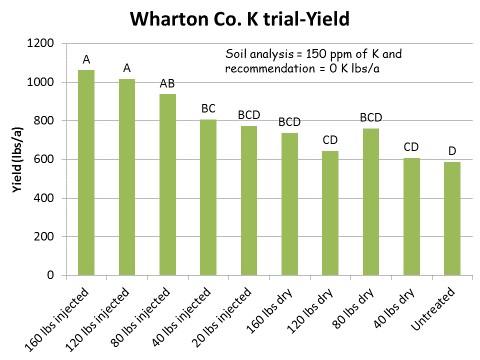

Once the soil test levels are known (preferably for a 0-6” and deeper samples), then the recommended potassium should be applied and incorporated (or injected) the meet the yield goal. Recent research in the Upper Gulf Coast suggests that the soil K threshold levels are likely on the low side. So, if your soil test levels are between 150-200 ppm (Melich III extraction), then growers should consider adding potassium as part of a maintenance program. Yield results from broadcast incorporated and injected applications of KCl have increased yields in most years with the injected applications providing more consistent yield increases. See Figure 7 below.

Figure 4. Senescing leaves that have other fungal leaf spots (insert: Alternaria sp., (right); Semphyllium sp. (left).

Figure 5. Early developments of potassium deficiency symptoms (left) from plots with no potassium applied and cotton plots that received 80 lbs of potassium (injected) prior to planting cotton. Wharton County, TX.

Figure 6. Secondary pathogen infection on cotton in Williamson county, TX that had previously expressed potassium deficiency symptoms due to low soil potassium levels (upper left corner) compared to cotton that received 120 lbs/a of potassium (lower right corner).

Figure 7. Cotton yield response to soil applied potassium (dry fertilizer incorporated and liquid fertilizer injected) four weeks before planting cotton in 2013 in Wharton county, TX. Soil K analysis levels were at the current threshold of 150 ppm, but yields increased with additional potassium applied, especially through the injected applications.

Thomas Isakeit, Ph.D.

Professor and Extension Plant Pathologist

College Station, TX

t-isakeit@exchange.tamu.edu