I’m not sure if “web sites” and “blog posts” are still a thing in 2022, but I am too old to start a TikTok channel so keeping this site updated will probably have to do. I will add posts on some of our lab’s papers from the last few years, and basically try to keep this place more up to date.

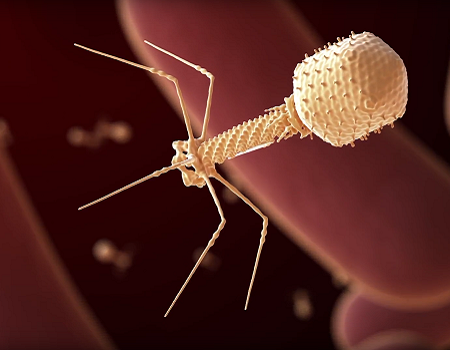

Here is an update with one of our more recent papers, a followup on the 2016 Patterson case intervention. This was described in a 2017 paper, but at the time there was little information on the phages used or the pathogen strain. A paper published earlier this year in Nature Communications follows up on this, describing the phages, pathogen and their evolution during treatment. The gist of the study is that all of the first-line phages used were closely related, and that this is probably why bacterial resistance to the treatment emerged so quickly, as soon as a few days after the start of treatment. Exactly why the treatment seemed to work is still not clear; it could be that the phage caused an initial reduction in bacterial load that could then be dealt with by the immune system, or that the remaining phage-resistant mutants were somehow less virulent, or a combination of these factors.

The Nat Comms paper is available here, and is also covered in this Nature Community blog post, which has a bit more background.