Featured Articles

Ryberg WA, Hill MT, Painter CW, Fitzgerald LA. 2013. Landscape Pattern Determines Neighborhood Size and Structure within a Lizard Population. PLoS ONE 8(2): e56856. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056856.

Ryberg W., Hill M.T., Painter C.W., Fitzgerald L.A. (2015). Linking irreplaceable landforms in a self-organizing landscape to sensitivity of population vital rates for an ecological specialist. Conservation Biology 29(3):888-898. DOI: 10.1111/cobi.12429.

Leavitt D.J., Fitzgerald L.A. 2013. Disassembly of a dune-dwelling lizard community due to landscape fragmentation. Ecosphere 4(8): 97. DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/ES13-00032.1.

Ryberg, W. Hibbitts, T.J., Walkup, M. Fitzgerald, L.A. 2016. Best Practices for Managing Dunes Sagebrush Lizards in Texas. Texas A&M University Institute of Renewable Natural Resources, Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences, Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collections College Station, Texas. iii-vii+ 83 pp.

Walkup, D. K., D. J. Leavitt, and L. A. Fitzgerald. 2017. Effects of habitat fragmentation on population structure of dune-dwelling lizards. Ecosphere 8(3):e01729. 10.1002/ecs2.1729

Chan, L., L.A. Fitzgerald, Zamudio K. 2009. The scale of genetic differentiation in the Dunes Sagebrush-Lizard (Sceloporus arenicolus), an endemic habitat specialist. Conservation Genetics 10:131-142.

Fitzgerald, L.A., C.W. Painter, D.A. Sias, H.L. Snell. 1997. The range, distribution and habitat of Sceloporus arenicolus in New Mexico. Final report to New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, Santa Fe, NM. 30 pp + appendices.

Fitzgerald, L. A., C. W. Painter, T. J. Hibbitts, W. A. Ryberg† and N. Smolensky*. 2011. The range and distribution of Sceloporus arenicolus in Texas. Submitted to Institute for Renewable Natural Resources, Texas A&M University for the Office of the Texas State Comptroller.

Background

Dunes Sagebrush Lizard (Sceloporus arenicolus)

The Dunes Sagebrush Lizard (DSL, Sceloporus arenicolus) is a small dune-dwelling lizard endemic to southeastern New Mexico and adjacent west Texas (Degenhardt and Jones 1972, Axtell 1988, Degenhardt et al. 1996, Fitzgerald and Painter 2009, Fitzgerald et al. 2011). Dunes sagebrush lizards are endemic to the shinnery oak sand dunes of the Mescalero-Monahans Sandhills ecosystem that forms a crescent-shaped arc of disjunct dunes through Andrews, Crane, Gaines, Ward and Winkler counties in Texas (Fitzgerald et al. 2011) and in Chaves, Eddy, Lea and Roosevelt counties in New Mexico (Laurencio and Fitzgerald 2010). The DSL is a habitat specialist. It only lives in sites characterized by bowl-shaped depression of sand (blowouts), and carries out its entire life cycle among interconnected blowouts and the vegetation around the perimeter of blowouts (Fitzgerald et al. 1997, Fitzgerald et al. 2005, Fitzgerald and Painter 2009, Hibbitts et al. 2013).

The DSL has been a species of conservation concern to government agencies and many stakeholder groups for at least two decades (Fitzgerald et al. 2012). It is of special interest to wildlife agencies in Texas and New Mexico because in addition to having a very restricted and naturally disjunct distribution, land use practices have contributed to fragmentation and loss of habitat (Smolensky and Fitzgerald 2011, Leavitt and Fitzgerald 2013, Ryberg et al. 2015). It was proposed for federal listing as endangered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in December 2010 (Federal Register December 14, 2010). The proposed rule was centered on a number of threats to the species’ habitat, with particular emphasis on the problems of shinnery oak removal by spraying of herbicides and habitat destruction and fragmentation caused by oil and gas development. In June 2012, the proposed rule was withdrawn, based on the US Fish and Wildlife Service assessment that the threats were being addressed by the implementation of the New Mexico Candidate Conservation Agreement (CCA) and Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances (CCAA), the Texas Conservation Plan (TCP), and the Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM) Resource Management Plan Amendment (RMPA) (Federal Register June 19, 2012).

View of shinnery oak dunes with blowouts at the Sand Ranch, Chaves County, NM. The foreground is habitat that was destroyed by herbicide spraying more than 20 years ago and never recovered. The shinnery oak dunes in the background are occupied by dunes sagebrush lizards.

Life History

Description

The DSL is a small phrynosomatid lizard. Males average 54.5 mm SVL and females average 53.8 mm SVL (Degenhardt et al. 1996). The dorsal coloration is light brown with an ill-defined pair of longitudinal lighter stripes extending down the sides of the torso. Males have large paired blue belly patches and occasionally have scattered blue scales on the throat. Females develop orange markings on the sides of the face, neck, and body when they become gravid.

Reproduction and Nesting

A radio-tagged female dunes sagebrush lizard that is gravid with her clutch of 3-5 eggs. This subject was part of a radio-tracking study to learn about migrations females make to nesting sites.

The DSL can be found active throughout the year; however, the activity peaks in spring and summer. Like most lizards, onset of reproduction is cued by increasing temperatures and day length in spring. Courtship and mating occurs mostly during May and June, which also corresponds to the peak activity period for the species. Like other members of their genus and family, female DSLs migrate out of their core home range to nest (Hill and Fitzgerald 2007). During the 2007 radio-tracking study 10 nesting sites were found and two nests were discovered with eggs. Females nested at night and dug their nest tunnels into the steep side of a blowout until they reached moist soil. Another nest was found in 2011 in a blowout (Ryberg et al. 2012). The observations, taken together, indicated females select nest sites close to the moisture horizon in the sandy soil and chose sites where sand grain size composition is relatively coarse compared to surrounding areas in their home range (Ryberg et al. 2012). Females may reproduce once or twice in a season, laying an average of 5 eggs per clutch in mid-June, and again in late July or early August (Fitzgerald and Painter 2009, Ryberg et al 2015). Hatchlings appear in early July and a portion will reach sexual maturity in their first spring (about 10 months of age). Individuals that hatch later or grow slower may not breed until their second spring. The lifespan of the DSL is 3-5 years.

Diet and Predators

The coachwhip (Masticophis flagellum) is a diurnal racer that feeds on lizards and other prey. This species is known to feed on dunes sagebrush lizards, including females making their nesting migrations.

The DSL is a sit-and-wait ambush forager and its diet is typical of small North American lizard species, consisting mostly of ants, grasshoppers and crickets, spiders, beetles, and other arthropods (Fitzgerald and Painter unpublished data). A number of predators prey on DSLs, including a variety of snake species, avian predators such as loggerhead shrikes (Hathcock and Hill 2012), and mammalian predators. One radio-tracking study found coachwhip snakes (Coluber flagellum) consumed 20% of radio-tagged gravid females (Hill and Fitzgerald 2007).

Evolutionary History, Systematics, and Taxonomy

The DSL when first discovered was considered a disjunct population of S. graciosus, the Sagebrush Lizard. It was formally described as a new subspecies, S. graciosus arenicolus (Degenhardt and Jones 1972), but elevated to species status (S. arenicolus) by Collins (1991) because the DSL was identified as a morphologically distinct, allopatric subspecies. Later studies of phylogenetic systematics of lizards in the genus Sceloporus supported the identity of the DSL, but finer scale resolution of relationships among the sagebrush lizards, including the DSL was still lacking (Wiens and Reeder 1997, Wiens et al. 2010). A recent study by Chan et al. (2013) used modern phylogenetic analyses of DNA sequence data and reviewed taxonomic literature on the morphology of the DSL. Their study demonstrated the DSL is morphologically, behaviorally, and genetically distinct from its nearest relatives and should be considered a species. An estimate of divergence times showed the DSL, together with its most closely related Sagebrush Lizard populations, was about 2,330,000 years old, and the average age of DSL lineages was about 490,000 years old. It is believed that the DSL co-evolved with formation of the Mescalero-Monahans Sandhills ecosystem during the Pleistocene (Chan et al. 2009), presumably becoming specialized to live in the dune environment where it diverged in isolation from its Sagebrush Lizard ancestors.

Geographic Distribution

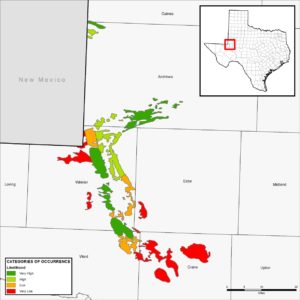

At the time the DSL was described, its known distribution in Texas and New Mexico was restricted to only a few locations. A three year distribution study in New Mexico was the first effort to document the geographic range in that state (Fitzgerald et al. 1997). The first survey efforts to better understand the distribution of DSL in Texas occurred in 2006 and 2007; however, DSL were only captured at 3 of 27 sites surveyed (Laurencio et al. 2007). In 2011, a major survey of the range of the DSL in Texas was undertaken (Fitzgerald et al. 2011). The 2011 study completed 51 surveys at 50 sites, and documented presence of the DSL at 28 of the 50 sites. Additionally, a map was produced that categorized areas of the species’ range in Texas ranging according to Very High, High, Low, or Very Low Likelihood of Occurrence (see below). In their report on the range and distribution of the DSL in Texas, Fitzgerald et al. (2011) concluded that habitat quality and historical patterns of occurrence influenced the likelihood of occupancy or occurrence of the DSL in habitats distributed across the landscape. In Texas, the DSL is currently known to persist in Andrews, Gaines, Ward, and Winkler Counties. Populations have not been observed in Crane County since 1970 (Fitzgerald et al. 2011), but a current translocation experiment is taking place in Crane County near the old historical locality.

Texas Conservation Plan Permit Area/Likelihood of Occurrence Map created by Dr. Toby Hibbitts, TAMU Research. The colors in the legend and corresponding map represent Likelihood of Occurrence Class; red is Very Low (0‐25 percent probability of DSL occurrence), orange is Low (25‐50 percent probability of DSL occurrence), light green is High (50‐75 percent probability of DSL occurrence), and dark green is Very High (75‐100 percent probability of DSL occurrence).

Atlases of historical localities and habitat for dunes sagebrush lizards in New Mexico and Texas

To aid in understanding the distribution and habitat of the dunes sagebrush lizard, atlases of localities were produced for New Mexico and Texas (Laurencio and Fitzgerald 2010, Laurencio et al. 2007). The atlases show historical localities, and make it easy and intuitive to see the boundaries of suitable habitat. The atlases are at least as useful as probability-based suitability models in terms of visualizing extent of occupied habitat. Atlases allow direct visualization of the extent of shinnery oak dunes in relation to known occupied historical localities. This is why the Hibbitts map has proven to be very reliable. Probablilty-based models based on remote sensing data tend to overestimate the extent of suitable habitat in some areas, and underrepresent occurrence of sandy areas in others. Click links below to download.

Laurencio, L.R. and L.A. Fitzgerald1. 2010. Atlas of distribution and habitat of the dunes sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus arenicolus) in New Mexico. Texas Cooperative Wildlife Collection, Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-2258. ISBN# 978-0-615-40937-5.

Laurencio L.R., Laurencio D. and L. Fitzgerald. 2007. Atlas of potential habitat for Sceloporus arenicolus in Texas: Appendix 1 of Fitzgerald, et al. 2007. Geographic Distribution and Habitat Suitability of the Sand Dune Lizard (Sceloporus arenicolus) in Texas. Final report prepared for Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Habitat

The habitat requirements of the DSL have been studied in detail at several spatial scales ranging from microhabitat use (Hibbitts et al. 2013) to the characteristics of blowouts (Fitzgerald et al. 1997), and finally to regional landscape scale patterns of habitat configuration (Ryberg et al. 2013). The DSL is a habitat specialist, occurring only in shinnery oak sand dunes with blowouts. The DSL utilizes microhabitats with steeper slopes and more open sand than expected by chance (Hibbitts et al. 2013). The largest size classes of blowouts (those that were large in area and deep) were most often found to be occupied by DSL (Fitzgerald et al. 1997). The size and configuration the complexes of these blowouts on the landscape also are associated with larger populations of DSL (Ryberg et al. 2013).

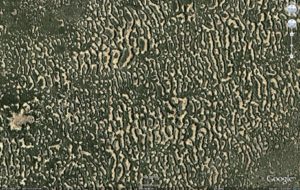

Aerial image from Google Earth of a large expanse of shinnery oak dunes at the Sand Ranch, Chaves Co. NM, an Area of Critical Environmental Concern, illustrating the interconnected mosaic of blowouts in shinnery oak dunes. This area is occupied by the dunes sagebrush lizard.

A view of blowouts in shinnery oak dunes

This view of shinnery oak dunes with blowouts shows the bumpy (rugose) topography with interconnected blowouts among shinnery dunes, which is the only habitat used by dunes sagebrush lizards.

Population Ecology

Population dynamics

Previous studies in New Mexico have examined how population dynamics of the DSL are linked to the shinnery oak sand dune landscape. A five-year mark-recapture study in practically undisturbed habitat in New Mexico yielded much information on population dynamics of the DSL. The research showed that among six independent trapping grids in contiguous shinnery dune habitat, the lizard population could be conceived as living in neighborhoods of individuals that created source-sink dynamics across that landscape (Ryberg et al. 2013). Neighborhood size was associated with contiguity of the habitat, slope, and soil compaction, and larger neighborhoods acted as net exporters of individuals (sources) and smaller neighborhoods as net importers (sinks). Annual survival at the sites varied from 0.46 to 0.74 annually, recruitment ranged from 0.09 to 0.16 per site, but the realized rate of population growth was stable (indistinguishable from 1) at each site. With the same mark-recapture study, Ryberg et al. (2015) also examined the linkages between configuration of the blowout areas and survivorship of adults and juveniles, and fecundity of females (population vital rates). They showed that the landscape configuration influenced population dynamics with the population growth rate (λ) being sensitive to proportional changes to fecundity and juvenile survival in irregular blowouts with more edge, while in more regularly shaped blowouts with less edge, the population growth rate was more sensitive to proportional changes to adult survival (Ryberg et al. 2015). Finally, population estimates of the DSL were carried out at multiple sites in New Mexico during two field seasons by Smolensky and Fitzgerald (2010), using both distance sampling and total removal plots. DSL densities ranged from 4.6/ha using distance sampling methods to 30/ha using total removal plots.

Population genetics

Collecting genetic samples in the field

A study of genetic population structure of the DSL (Chan et al. 2007, Chan et al. 2009) found three genetic clusters corresponding to north, central, and southern regions of the species’ entire range across southeastern New Mexico and West Texas. The study also showed limited gene flow between two sites in the northern and central populations, as well as from the southern population to the western central population. Migration estimates between the genetic populations were low, although there is a suggestion of asymmetric migration from the north to the central region.

Effects of Fragmentation

Construction of networks of caliche well pads and roads for oil and gas development within the shinnery oak sand dune landscape results in the loss and fragmentation of shinnery oak sand dune habitat. Research on the DSL has identified potential correlates between oil and gas development and lizard abundance. Using data from visual transect surveys and measurements of oil pad density Sias and Snell (1998) found a significant, negative correlation between lizard abundance and oil pad density. Additionally, Smolensky and Fitzgerald (2011) identified a positive association between lizard abundances and the amount or extent of blowouts within the surrounding habitat, although they did not find a linear relationship between abundance of DSLs and total area of caliche well pads and roads. To more fully investigate the effects of fragmentation on populations of the DSL, a large mark-recapture study was undertaken near Loco Hills, NM. Populations in fragmented habitat had skewed demographic structure and very low abundance compared to populations in unfragmented habitat, and completely disappeared from sites where they were historically documented. On fragmented grids, the yearly capture rate started at 0.0019 captures/trap-day in 2009 and 2010 and decreased every year until, in 2013, zero DSLs were captured on fragmented grids (Walkup et al. 2017). This disappearance of populations of DSL contributes to community disassembly in fragmented habitats, likely due to changes in the landscape configuration in fragmented sites which had fewer large dune blowouts than unfragmented sites (Leavitt and Fitzgerald 2013).

Translocation Research

A hatchling dunes sagebrush lizard that emerged from a nest at the translocation site in 2016.

Conservation introductions are purposeful translocations intended to benefit biodiversity. The DSL was known from one locality in Crane County, TX in 1970, but has never been found there since. The habitat conditions appear highly suitable for the lizard. Repeated surveys in the past 5 years have never detected DSL. Part of our current research involves experimental translocations of DSL to an area with highly suitable habitat near the 1970 historical locality. This research, which is part of the doctoral dissertation research by Mickey Parker, Texas A&M University, is in it’s second year. Soft-releases, with a male and multiple females in enclosures within the habitat, have been carried out in 2016 and 2017. A landscape scale trapping grid allows us to conduct a mark-recapture study at the site to estimate population growth, survivorship, and dispersal in the translocated population.

Publications on the dunes sagebrush lizard

Chan, L., Zamudio K., L.A. Fitzgerald. 2007. Primer note. Characterization of microsatellite primers for the endemic sand dune lizard, Sceloporus arenicolus. Molecular Ecology Notes 7:337-339.

Chan, L., L.A. Fitzgerald, Zamudio K. 2009. The scale of genetic differentiation in the Dunes Sagebrush-Lizard (Sceloporus arenicolus), an endemic habitat specialist. Conservation Genetics 10:131-142. (pdf)

Chan L.M., Archie J.W., Yoder A.D., Fitzgerald L.A. 2013. Review of the systematic status of Sceloporus arenicolus (Degenhardt and Jones 1972) with an estimate of divergence time. Zootaxa 3664 (3): 312–320.

Fitzgerald, L.A., C.W. Painter, D.A. Sias, H.L. Snell. 1997. The range, distribution and habitat of Sceloporus arenicolus in New Mexico. Final report to New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, Santa Fe, NM. 30 pp + appendices. (pdf)

Fitzgerald, L. A., and C. W. Painter. 2009. Dunes Sagebrush Lizard (Sceloporus arenicolus). Pages 198-120 in L. C. Jones, and R. E. Lovich, editors. Lizards of the American Southwest: A Photographic Field Guide. Rio Nuevo Publishers, Tuscon, AZ.

Fitzgerald, L. A., C. W. Painter, T. J. Hibbitts, W. A. Ryberg† and N. Smolensky*. 2011. The range and distribution of Sceloporus arenicolus in Texas. Submitted to Institute for Renewable Natural Resources, Texas A&M University for the Office of the Texas State Comptroller. (pdf)

Fitzgerald L.A., Allen T., Chan L.M., Chopp J., Dixon J.R., Ferguson G., Gluesenkamp A., Hibbitts T.J., Hill D., *Hill M.T., Howard R., *Leavitt D.J., Miles D.B., Painter C.W., Pifer E., †Ryberg W.A., Sears M., Snell H.L. 2012. The Research Program on Sceloporus arenicolus: Integration of findings, gaps in knowledge, and priorities for conservationoriented research. Report to Center of Excellence for Hazardous Materials Management (CEHMM), Carlsbad, NM. (PDF)

Hibbitts, T.J., W.A. Ryberg, C.S. Adams, A.M. Fields, D. Lay, and M.E. Young. 2013. Microhabitat selection by a habitat specialist and a generalist in both fragmented and unfragmented landscapes. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 8: 104-113.

Hibbitts, TJ, Fitzgerald L.A., Walkup D., Ryberg W. 2017. Why didn’t the lizard cross the road?: Dunes Sagebrush Lizards exhibit road avoidance behaviour. Widlife Research. http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/WR16184.

Laurencio, L.R. and L.A. Fitzgerald1. 2010. Atlas of distribution and habitat of the dunes sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus arenicolus) in New Mexico. Texas Cooperative Wildlife Collection, Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-2258. ISBN# 978-0-615-40937-5. 1Corresponding author.

Leavitt D.J., Fitzgerald L.A. 2013. Disassembly of a dune-dwelling lizard community due to landscape fragmentation. Ecosphere 4(8): 97. DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/ES13-00032.1. (pdf)

Leavitt D.J., Acre Matthew R. 2014. Sceloporus arenicolus (Dunes Sagebrush Lizard). Activity patterns and foraging mode. Herpetological Review 45(4): 699-700.

Painter C.W., Fitzgerald, L.A., D.A. Sias, L. Pierce, H.L. Snell. 1999. Management Plan for Sceloporus arenicolus in New Mexico. Management Plan for New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, Bureau of Land Management, US Fish and Wildlife Service. 45 pp + 9 appendices.

Romano A. J., D. J. Leavitt, C. M. Schalk, D. E. Dittmer, and L. A. Fitzgerald. 2014. Vertebrate by-catch of pipeline trenches in the Mescalero-Monahans shinnery sands of southeastern New Mexico. Prairie Naturalist 46(2):104-105.

Ryberg, W.A., M.T. Hill, D. Lay, and L.A. Fitzgerald. 2012. Observations on the reproductive and nesting ecology of the Dunes Sagebrush Lizard (Sceloporus arenicolus). Western North American Naturalist 72(4) 582-585.

Ryberg WA, Hill MT, Painter CW, Fitzgerald LA. 2013. Landscape Pattern Determines Neighborhood Size and Structure within a Lizard Population. PLoS ONE 8(2): e56856. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056856. (pdf)

Ryberg W., Fitzgerald L.A. 2015. Landscape composition, not connectivity, determines metacommunity structure across multiple scales. Ecography 38 01-10. doi: 10.1111/ecog.01321.

Ryberg W., Fitzgerald L.A. (2015). Sand grain size composition regulates subsurface oxygen and distribution of an endemic psammophilic lizard. Journal of Zoology: 295, 116–121.

Ryberg W., Hill M.T., Painter C.W., Fitzgerald L.A. (2015). Linking irreplaceable landforms in a self-organizing landscape to sensitivity of population vital rates for an ecological specialist. Conservation Biology 29(3):888-898. DOI: 10.1111/cobi.12429. (pdf)

Ryberg, W. Hibbitts, T.J., Walkup, M. Fitzgerald, L.A. 2016. Best Practices for Managing Dunes Sagebrush Lizards in Texas. Texas A&M University Institute of Renewable Natural Resources, Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences, Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collections College Station, Texas. iii-vii+ 83 pp. This document was prepared by the Dunes Sagebrush Lizard Research Team at Texas A&M University. (Wade Ryberg, Danielle Walkup, Megan Young, Lee Fitzgerald, and Toby Hibbitts) with assistance from Texas A&M Institute of Renewable Natural Resources’ Geospatial Analysis Team (Brian Pierce, Lydia Cao, Kevin Skow, Amanda Dube, and Lauren Johnson) and Director, Roel Lopez. For information contact (waryberg@tamu.edu). (pdf)

Smolensky, N. and L.A. Fitzgerald. 2011. Population variation in dune-dwelling lizards in response to patch size, patch quality, and oil and gas development. Southwestern Naturalist 56(3):315-324.

Smolensky, N. and L.A. Fitzgerald. 2010. Distance sampling underestimates population densities of dune-dwelling lizards. Journal of Herpetology 44:372-381.

Walkup, D., Fitzgerald, L.A., Leavitt DJ, Ryberg WA. 2013. Effects of landscape fragmentation on the Mescalero Dune landscape and populations of the dunes sagebrush lizard, Sceloporus arenicolus. Bureau of Land Management, Carlsbad NM. 159 pp.

Walkup, D. K., D. J. Leavitt, and L. A. Fitzgerald. 2017. Effects of habitat fragmentation on population structure of dune-dwelling lizards. Ecosphere 8(3):e01729. 10.1002/ecs2.1729. (pdf)

Young, M.E., Ryberg, W. Fitzgerald L.A., Hibbitts, TJ. (in press). Fragmentation alters home range and movements of the dunes sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus arenicolus). Canadian Journal of Zoology.