Under a contract with the National Trends Network, a national monitoring network sponsored by the United States Department of Agriculture, we operate a monitoring site on the south rim of North Ceta Canyon. At Cañonceta we measure ground-level, atmospheric ammonia concentrations, wet deposition, and dry deposition.

Why ammonia? Mainly because in the presence of atmospheric moisture, ammonia can dissolve into that moisture and then react with other airborne species – mainly sulfate and nitrate – to form fine particles. These particles scatter light pretty efficiently, so at high enough concentrations, ammonium sulfate and ammonium nitrate can reduce visibility. At even higher concentrations, fine particles have been associated with impairment of human health. Finally, these fine particles can travel tremendous distances, and wherever they ultimately land, they carry their ammonia cargo with them.

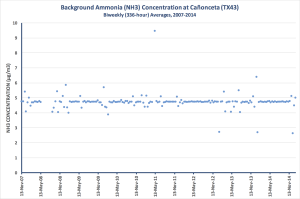

By itself, airborne ammonia can be thought of as a health hazard in its own right, but the higher concentrations required to pose such a hazard typically occur only in occupational settings or around fertilizer spills (railways, anhydrous tank-trailers, etc.). The ammonia concentrations we have measured at Cañonceta (see chart at left) are far too low to pose such a threat; ~5 micrograms per cubic meter is a factor of 5-7,000 lower than the occupational guidelines published by the federal government of the U. S.

A gorgeous view of North Ceta Canyon, photographed from the roof of the instrument shelter at Cañonceta.

Ammonia is also very “sticky” and reactive, so when it encounters a wet surface such as a pond or a dewy blade of grass or leaf, it readily dissolves and is available to participate in the surrounding biochemical systems. Out in the countryside, that usually means that ammonia is a natural source of fertilizer for grasses, forbs, trees, and brush. Some scientists in Colorado have determined that the mix of vegetation in Rocky Mountain National Park has shifted away from wildflowers and toward sedges because of nitrogen and sulfur deposition in the park. No doubt some of that nitrogen has come in the form of either gaseous ammonia or ammonia-based particles that drift into the Park and are scrubbed out of the atmosphere by rain and snow.