Only a few short months ago, the sheep and goat market was strong. On average the market is down $0.50 per pound since April. Consumer demand is continuing to grow for lamb and goat meat. However, demand is not our problem. Supply is our problem!!!

To be more clear, continuous supply of domestic lamb and goat to the market is the problem. Cheaper imported lamb and goat meat is an added issue but this won’t be discussed in this month’s article.

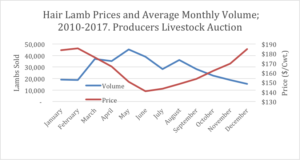

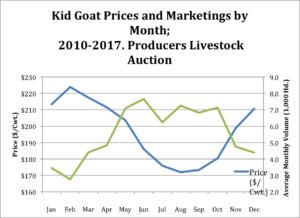

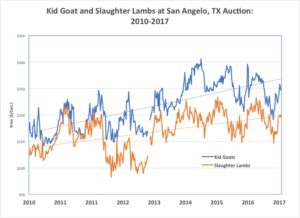

We all hear about specific holidays that impact the sheep and goat market. But the biggest impact on the market is supply. We consistently see strong markets in the winter when supply of light-weight slaughter lambs and goats are low. And we consistently see a reduction in the overall market in the summer when supplies are high.

Below are two figures produced by colleagues of mine at the Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center in San Angelo that clearly show the negative relationship between supply and demand for lambs and goats.

Complete reports can be found at: https://sanangelo.tamu.edu/extension/west-central-agricultural-economics/.

According to USDA, 85 percent of lambs are born in the first 5 months of year. This is the root cause of our supply and demand issues. Sheep and goats are seasonal breeders. They tend to breed in the fall for late winter and spring lambs and kids. Very few lamb and kids are born in the summer months. However, in the spring, some sheep and goats will breed for fall lambs and kids.

On a similar note, I led the development of a white paper titled “Seasonality of the U.S. Lamb Industry.” The report can be found at: http://lambresourcecenter.com. This white paper provides in depth detail about this subject. It is a complicated issue and most all the major factors involved are discussed. But the take home message is “we need more farmers and ranchers to market lambs during atypical times to even out supply.” Both consumer and producer benefit from a stable market.

Texas is positioned very well for aseasonal lamb and kid goat production. Compared to other parts of the nation, we have mild weather and can produce adequate feed resources during the winter. Especially, if ranchers have access to cereal forages and/or native winter grasses and weeds.

For hair sheep and meat goat producers, I recommend to put out the rams/bucks with females the end of March or early April. Not all females will breed out of season, especially, if they are under weight or hae lambed/kidded in the previous 45 days. September and October born lambs/kids are ideal to hit the winter market. Also, there tends to be more feed resources in the fall than the winter. Bucks could be left in with ewes/does through fall or could be removed for 60 days or more to provide a break in lambing.

For wool sheep producers, I recommend putting the rams with the ewes in June for early winter-born lambs. These lambs would then be ready for market in April/May. Wool lambs are well suited for the traditional lamb feeding sector and bring premiums when both lamb feeders and non-traditional buyers are bidding.

It is extremely crucial that non-seasonal lamb or goat producers determine if they can produce or get access to cost effective feed resources during the fall and winter. Without quality feed, sheep and goats will struggle to produce healthy, productive offspring regardless of the season.

To provide feedback on this article or request topics for future articles, contact me at reid.redden@ag.tamu.edu or 325-653-4576. For general questions about sheep and goats contact your local Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service county office. If they can’t answer your question, they have access to someone who can.