Imports. Friend or Foe?

By now you know that I am a strong proponent of eating and promoting the consumption of lamb and goat meat. Bottom line, it is delicious, but the reasons to include lamb or goat in your meal rotation do not end there. It is nutritious and versatile in the ways it can be prepared. And as producers I believe it is important for us to be advocates of our own products.

When we cook and eat lamb and goat ourselves, we also become better advocates for it. I can’t count the number of times, I’ve heard “I only like lamb when Reid cooks it.” Over time, the fear of something different and we gain another advocate. Be Patient!

As a routine customer, I’m always inquiring about the origin of the product. Often, they are sourced from another country. Imported lamb is perceived by many consumers as exclusive and superior products. In reality, most imported products are purchased by American restaurants or grocers because of price and availability. Currently, domestic products are sold by wholesalers at roughly double the price of imported products.

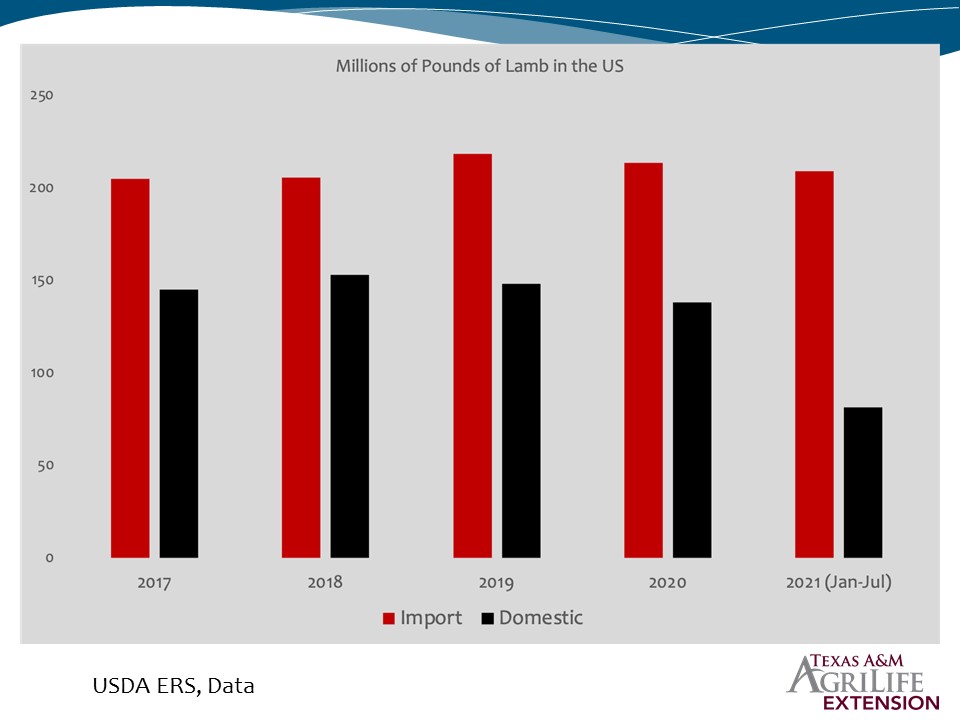

Over the last decade, half the lamb and a third of the goat meat consumed in the US are imported. So far in 2021, lamb imports are nearly double US production (Figure 1). The top two countries that provide most of the lamb and goat meat are Australia and New Zealand, but that might be about to change.

In September of 2020, the Biden administration lifted a 30-year-old ban on British lamb and mutton from being imported into the US. The ban was originally created in response to the first outbreaks of BSE, commonly known as mad cow disease. With U.S. markets off the table until now, most of their exports were going to Europe. While it is unclear how this will affect American producers, one silver lining is that lifting of the ban also allows for the import of United Kingdom (UK) sheep genetics, such as semen and embryos.

The UK is the third largest exporter of sheep meats globally, behind Australia and New Zealand. I had the privilege of touring the UK sheep industry in the fall of 2019. During this tour, we learned that the British export roughly half of their lamb during peak production and import a similar equivalent of lamb from New Zealand during the off season. This “trade off” seems to work given that the UK and New Zealand have similar production systems but are located in different hemispheres.

I’d anticipate that British lamb will likely be marketed at similar value to other imported lamb products. In theory, more supply will bring down lamb prices at the food counter and inevitably reduce value of lambs at the farm gate. But I’ve come to realize that the US lamb market is complex and difficult to project.

The US lamb industry grossly undersupplies the demand and it is unlikely that we will grow to a level to meet this demand any time in the near future. While I’d like to see our industry expand, it is more likely that we will see a further reduction in overall lamb and goat production. Both from farmers exiting the industry and operations that reduce flock or herd size. Furthermore, the rapidly growing non-traditional market prefers to harvest lambs at 25 to 50 percent lighter weights than conventional markets. Harvesting lighter lambs results in even lower volume of domestic lamb production. To keep a supply of lamb for the growing American appetite for lamb, we are likely going to need more imports.

In my opinion, the negative impact of imports are due to a discrepancy in value. Imports tend to be cheaper for a variety of reasons. First, emerging domestic demand has driven up the market for lambs and goats above global prices. This is good for sheep farmers but it also creates opportunity for imports to gain a stronger foothold in traditional channels. Second, the imports tend to have lower costs of production due to limited predation, access to more animal health products, economy of scale, government support programs, etc.

The goat market isn’t as affected by imports as they lack a sizable volume of goat meat for export. Goat meat imports also come from Australia and New Zealand; however, their goats tend to be feral or very extensively managed. Based on my impression, export demand has impacted their national herd size and further long-term exports appears to be unsustainable. As an example, I have a friend in Australia that is proud to have successfully exterminated goats from their farm, as if they were pests.

In summary, the US lamb and goat industry is very much influenced by global trade. We need imported product to satisfy US demand and continue to grow the American appetite for lamb and goat meat. However, imports have a competitive advantage due a lower cost of production than US sheep and goat producers. I will be very interested to see how the markets react to future imports. What is still in our control though, is how we can be better advocates for lamb and goat meat. We’ll just have to take a page from Blue Bell’s playbook and “eat all we can and sell the rest.”

To provide feedback on this article or request topics for future articles, contact me at reid.redden@ag.tamu.edu or 325-657-7324. For general questions about sheep and goats, contact your local Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service county office. If they can’t answer your question, they have access to someone who can.