Precipitation, Parasites, and Prussic Acid

As I am writing this article, the temperature dropped 40 degrees overnight and it is raining. The abundance of rain over the last two months has been a welcome change from the dry hot summer. However, ranchers are keenly aware that changes in the weather bring “good” and “bad” alike.

In September, the rains came with warmer weather and there was an explosion of warm season grasses and weeds. The perennial warm season grasses shot up and went to seed in a matter of days. In addition, a wide-variety of weeds sprang up from any bare ground uncovered by grasses. Unfortunately, some of these weeds are toxic to sheep and/or goats.

I received numerous reports from ranchers with concerns of toxic plants. However, with so many new plants available to the animals, it is very difficult to determine which plant is the likely culprit. In most cases, the animals were “naïve” to these plants because they had not seen them before. Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service has published a book called “Toxic Plants of Texas.” Every rancher should have a copy of this book.

Another lurking issue that occurred from this late summer rains was internal parasites. Typically, internal parasites, specifically Haemonchus Contortus, are an issue in the spring and early summer. Young animals are more susceptible to parasites in the summer/fall because their immune system is not as able to suppress them.

Animals under 1 year of age have a higher nutritional demand for growth and their immune system may not have the sufficient nutrients to function, similar to an adult. Also, these young animals may not have been exposed to a parasite challenge during a dry year, and their immune system is “naïve” to them. It can take weeks for the immune system to fight off a new challenge. In some cases, the parasites get the upper hand and the animals may succumb to the parasites.

But this is not always a bad thing. At the research station in San Angelo, we used this parasite challenge to identify the animals that are better able to maintain low fecal egg counts when their flock/herd mates were not. This allows us to make better selection decisions on which animals to keep as replacements. It allows us to enter more data into NSIP (National Sheep Improvement Program) and improve the accuracy of the animals EBVs (estimated breeding values) for parasite resistance.

Fall is also a good time to conduct a fecal egg count reduction test. This is when you deworm animals with different drenches or drench combinations. You should have around 10 animals per treatment and the animals should be of similar age, condition, and production stage. Determine the fecal egg count for every animal at the time of drenching and the again 10-14 days later. Subtract the second fecal count from the first fecal count and divide by the first fecal count. Multiply by 100 and this will be percent effectiveness of the drench in your flock/herd. Effective dewormers should be at least 98% effective. Parasite resistance to drenches are different for every farm/ranch, so it is best to determine it on your own animals. Then, come springtime and parasites return, you will know which drenches to use to get the best parasite control.

If you follow the Texas A&M AgriLife Sheep and Goat Extension Facebook page you can stay up-to-date on projects such as the one mentioned above. We published 3 videos on the different classes of dewormers, shared the protocol to conduct a fecal egg count reduction test, and discussed copper oxide wire particles boluses.

Late summer rains did wonders for hay grazer that was planted to be grazed or harvested for hay. However, be cautious, when grazing this into the fall after a freeze. Prussic acid poisoning can occur. The withered parts of the plant and new growth contain higher concentrations of the toxic compound. After a freeze, it is best to keep animals off of a field until the wilted plants dry. And don’t turn out hungry animals onto a new field. It is best to fill them up on hay prior to turning them onto a new field.

Armyworms marched their way on fields and pastures with the summer rains and warm weather. But now that it has cooled off, both armyworms and internal parasites are going to be less of a problem until next year.

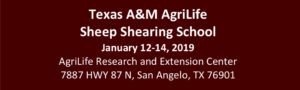

Today, I brought out the wool sweater to stay warm. This reminded me that registration is open for the Texas A&M Sheep Shearing, Wool Classing, and Animal Fiber 101 Schools. These schools are one of the highlights of the year for me.

We raised wool sheep but I did not grow up shearing sheep or classing wool/mohair. After attending a sheep shearing school in Montana, I developed a great appreciation for the fiber segment of the sheep and goat industry. More information about these schools can be found at: https://agrilife.org/sheepandgoat/.

To provide feedback on this article or request topics for future articles, contact me at reid.redden@ag.tamu.edu or 325-653-4576. For general questions about sheep and goats contact your local Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service county office. If they can’t answer your question, they have access to someone who can.