A grass plant is a collection of plant parts, like a tree or shrub, made up of growth units called tillers. Each tiller produces roots and leaves. Vegetative tillers consist primarily of leaves, whereas reproductive tillers produce a stem, seedhead, roots, and leaves. The basal area of the stem, where roots often arise, is the crown. All native perennial grasses reproduce by vegetative means. New tillers are formed from pre-existing or newly formed buds. Seed production may be valuable, but is not always necessary for population maintenance.

The crown usually has a number of buds (growing points) that produce new tillers and roots. New tillers are anatomically and physiologically connected to older tillers. Therefore, several connected tillers may all live and share resources like water, carbohydrates, and nutrients. If one tiller dies, an adjacent tiller with established roots and leaves usually lives, sustaining the species’ population. Some tillers stay vegetative their entire life span, while others become reproductive and produce seedheads. Whether a tiller becomes reproductive depends on the growing conditions, environment, and hormones produced in the grass.

For example, a reproductive tiller may remain vegetative if the terminal meristem bud is removed by grazing or fire. Vegetative growth, therefore, is favored by some disturbance, which reduces the number of seedheads produced and may stimulate the formation of new buds and new tillers. Vegetative tillers usually are less stemmy and more nutritious than reproductive tillers. Once a tiller has produced a reproductive seedhead, that tiller’s lifespan is over.

The amount of buds that exist on a single grass individual is referred to as the bud bank. The bud bank is made up of active and dormant buds. These buds are waiting for an environmental cue to become activated and to start to developing into a tiller. The bud bank density is the driving force behind a species response to grazing, drought, or fire. These buds also serve as carbohydrate reserves that are in the roots and crown and serve as growth points for spring or in response to aboveground disturbances. These carbohydrate reserves also are necessary for plant respiration during winter dormancy as the belowground buds remain alive providing energy for the plant to maintain itself until photosynthesis in the late winter/early spring take over.

Quantifying and describing the bud bank densities for our dominant Texas grasses is key to pairing the appropriate range management strategy. For example, season of burn, timing of grazing, grazing rotations, grazing intensity, fire return interval, etc… can all affect the bud bank of perennial grasses differently. Employing strategies that maxime the bud bank densities of native, perennial grasses is key to maintaining healthy native grass populations, plant diversity, and plant community resiliency.

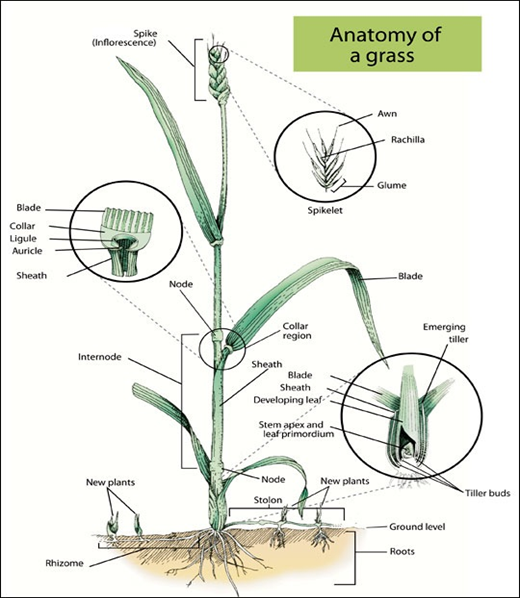

A grass plant is a collection of plant parts, like a tree or shrub, made up of growth units called tillers. Below, Figure 1 shows a reproductive grass tiller.

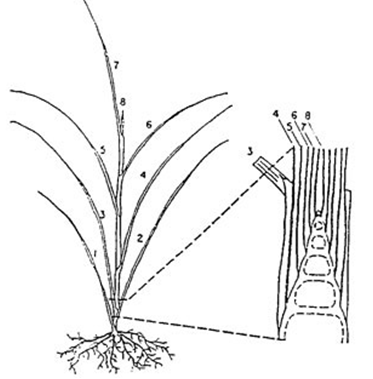

A simplified vegetative grass tiller. Leaf 1 is oldest and leaf 8 is just being exerted. The enlarged area of the crown shows the apical meristem that produced the leaves. New leaves push up from the center of the rolled tube portion of the first leaf; the growth is similar to the extension of a telescope. The growing point (apical meristem) is at or near the soil surface where leaves form, protected from grazing.

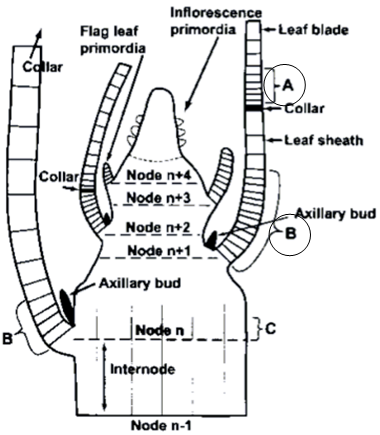

Cross section of the crown and tillers. ‘Node n’ is the oldest and ‘Node n+4’ is just forming. (A) Blade intercalary meristem, where blade cells divide and elongate. (B) Sheath intercalary meristem, where sheath cells divide and elongate. The shoot apex lays down cells that can form into a variety of structures.

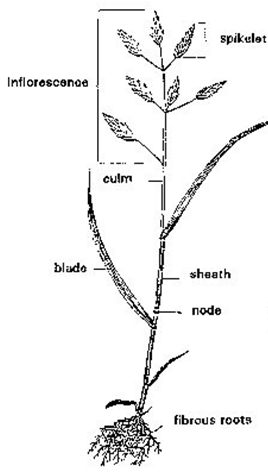

A reproductive grass tiller. This tiller has a stem (or culm) and seedhead that differs from the vegetative tiller. Intercalary meristematic tissue at the base of the leaf blade, above the ligule, is the area where cells divide so the leaf can extend.

The basic repeating unit of growth of a tiller is the phytomer. It consists of a node, an internode, a leaf sheath, a leaf blade, and an axillary bud. These structures arise from the area called the crown.